EXXON VALDEZ

OIL SPILL

History & Mission

The 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill (EVOS) was a manmade disaster in which an oil tanker ran aground and spilled 11 million gallons of crude oil into the pristine Prince William Sound. For over 20 years, this was the worst oil spill in U.S. history; oil covered over 1,300 miles of coastline. And more than 30 years later, like the pockets of crude oil you can find on the beaches, this page is here to serve as a reminder that even though there is an abundance of life in the intertidal zone, lingering oil from the 1989 Exxon Valdez Oil Spill still exists under the surface throughout Prince William Sound.

The oil spill killed unknown numbers of birds, mammals,

and sea life. These numbers are just estimates.

250,000

sea birds

2,800

sea otters

2,300

harbor

seals

250

bald

eagles

22

killer

whales

Billions of

salmon,

herring,

and their eggs

Lingering Effects

Still Remain

Some species have recovered, some have not. The full extent of the devastation is unknown because of a lack of prior baseline data. Of the $150 million Exxon was fined in their criminal plea agreement, $125 million was forgiven by the Courts, with the remaining $25 million being split between the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund and the National Victims of Crime Fund. For criminal restitution for the injuries caused to fish, wildlife, and the lands of the oil spill area, $100 million was paid to federal and state governments for restoration efforts. In the civil settlement, Exxon was fined $900 million, which it was ordered to pay in annual amounts with the purpose of restoring resources tha suffered substantial losses or declines as a result of the oil spill. The $900 million was used to create the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council (EVOSTC).

There remain lingering impacts to local subsistence users. Surface and subsurface oil remains in the intertidal zones, where shores are sheltered from winter storms. The negative impact to subsistence resources and harvest ability remains.

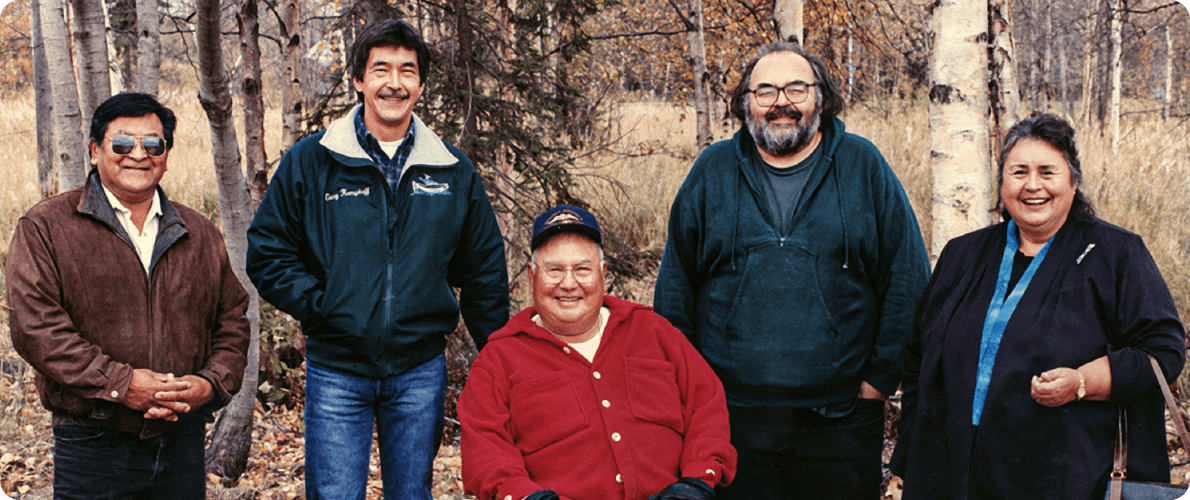

CRRC was formally incorporated in the crucible of the Exxon Valdez disaster and responded in every way with an extremely limited budget. CRRC

engaged with the EVOSTC following the Exxon settlement.

After the Disaster

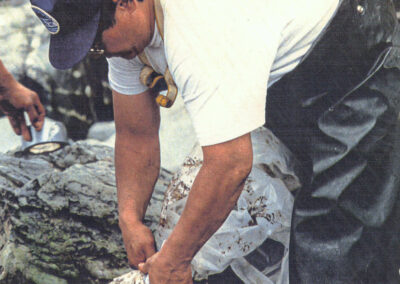

In the dark days that followed the Exxon Valdez disaster, CRRC organized responses to the loss of natural resources within the region. A few short years following the disaster, CRRC assisted the villages of Chenega and Tatitlek in developing early mariculture programs, using outside sources to assist in the development of oyster farming in Prince William Sound. Subsistence harvesters worked with scientists to gather samples of Native foods to test for oil contamination. Local residents took on roles that they had never anticipated in order to obtain information to allow them to make informed decisions regarding whether to continue to rely on the wild species they had traditionally used.

Many local Native experts of the region formed teams with the biologists studying paticular species, in order to exchange information and work together to gather data. In other cases, some communities engaged in enhancement and replacement projects. Sockeye salmon runs were temporarily created to replace natural fish runs that were damaged by the spill. CRRC engaged by spearheading clam beds on subsistence beaches, which had been first disrupted by the 1964 earthquake, and later—just when they were recovering—oiled by the spill. This enhancement effort resulted in significant new information regarding the life cycle of clams.

CRRC & EVOSTC

Between 1992 and 1997, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) constructed the Mariculture Technical Center (MTC) with EVOS criminal settlement money. The location of the facility in Seward was a direct result of CRRC and its communities wishing to continue working on clam restoration in response to food security and food safety issues. At the time of the spill, CRRC had already invested in developing hatchery technology for hard-shell clam production in a pilot facility at the Institute of Marine Science, now known as the Seward Marine Center. The success of developing the techniques led to the EVOS Trustee Council funding a clam restoration project from 1998 through 2001. To date, this is most likely the only EVOSTC-funded project that led to providing direct, valuable traditional foods for Native people in the region. Unfortunately, CRRC’s request to duplicate this work was rejected in October 2021 by the Science Panel, Public Advisory Committee, and EVOS Trustee Council.

When the MTC was completed, in 1997, the Marathon Native Tribe, now Qutekcak Native Tribe (QNT), with mutual agreements with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and the City of Seward, undertook the operation of the Mariculture Production Center (MPC) and agreed to cover maintenance costs of the MTC and MPC, located on City of Seward land, initially leased to the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Once the contract was given to QNT, the title of the facility was given to the City of Seward, where it remains today. The purpose of the MTC and MPC was to produce high-quality spat (bivalve larvae that are permanently attached to a surface) and aquatic plant seed for the Alaska mariculture industry. CRRC was heavily involved in this partnership, securing and providing funding and oversight of operations at the MTC. Shortly after the 1997 agreement, the parties recognized the growing abilities of CRRC to provide a strong scientific staff. In 2004, CRRC took over the complete operation of the facility and has been operating it ever since.

A man who lived in Chenega in 1989, and who still lives in the community, indicated that he has seen very little recovery of wildlife since the spill. He also stated that there is still oil in the ground, in the wildlife, and on the beaches. He said that fishing and hunting around his community is still not good.

A woman from Tatitlek, who was six years old in 1989 and is now a community leader, indicated that the spill still affects her life today, stating, “We are just now seeing more sea life in Tatitlek . . . gumboots [chitons], cockles, clams, and herring spawn still [have not] made a strong return.” She points out that if the spill had not happened,

Much of our traditional food would still be available to us. Without our traditional food very readily available, we aren’t hunting and gathering much. Our traditional ways are dying. The way we eat has changed drastically. Many of us rely on manufactured food and not wildlife or seafood. Our younger generations are not learning traditional ways. We still don’t see much herring spawn in Prince William Sound or gumboots.

When asked if she had seen any improvement since the spill, she said,

Little by little, we are very excited to have discovered gumboots, just a short walk from Tatitlek!

A young woman from Cordova, born after the spill in 1995, stated, “My Uppa [Grandfather] lost value in his herring permit. [He] lost millions of dollars to fishing that didn’t happen” as a result of the spill. She cited “generational trauma passed down” as a continued spill impact to her life. She also said, “If you dig down on some beaches, you will still find oil.” Even though she was born after the spill she said, she hears about it “regularly” from family members, and that it has negatively impacted their lives. She believes that her community would be richer, both in resources and monetarily had the spill not occurred. She listed salmon, herring, puffins, crustaceans, and killer whales as species still impacted by the spill. Like the other Cordova residents who responded to the survey, she cited better spill response preparedness as an improvement since 1989, but she cautioned that “the response team is only for certain areas and [certain] responsible parties.” Asked if the spill still impacts her community today, she responded, “Yes. We still have no herring, and our ecosystem is still so fragile.”

A Nanwalek resident indicated that the spill still affects his life but said he is “not current if some sea food is safe.”

He indicated that if it had not been for the spill, he would still be a commercial fisherman today. He said that the spill does not affect his family today as much as it used to but that his community relies more on store-bought food today because of the spill.

A woman from Port Graham stated “I worry about the oil effects on our subsistence food.” She indicated that she’s “not sure if any are safe to eat.” She said that if the spill had not happened, “we would have more fish and the fishing industry would be thriving.” She believes that the Port Graham cannery, which is now shut down, would still be operating today if the spill had not happened. She has strong opinions about how the spill settlement dollars have been used by the EVOS Trustee Council, saying, “The injustice of how funds are distributed by EVOS. [The money] does not even go to the affected communities.” She says that the Chugach region would be different had the spill not happened because “[The village corporation] lands would never have been sold, [and the] corporations running fisheries would have thrived.” She mentions several important harvest areas that still have oil in them, though also states that some subsistence resources impacted by the spill, including chitons and mussels, have finally come back.

A Closer Look

Whatever the future holds, it is certain that the changes the Chugach region and its people have experienced since the first contact with Europeans will be compounded by climate change. Through continued partnerships with our Tribes, CRRC is able to gather collective wisdom and Traditional Knowledge and give it a voice in order to foster a shared understanding of the current climate-related issues. We can bring the wisdom of the past to the interpretation of what is happening today to illuminate the work that needs to be done in the future.