Trumpeter and Tundra Swans

Cygnus buccinator (Trumpeter Swan)

Interested in reading the “Bird Ethnography of the Chugach Region” book?

Trumpeter and Tundra Swans

Cygnus buccinator (Trumpeter Swan)

uquerpak (LCI), uquirpak (PWS), GAXtl’ (Eyak)

Cygnus columbianus (Tundra Swan)

Qugyuk (LCI), qaturyuaq (PWS), GAXtl’ (Eyak)

Description

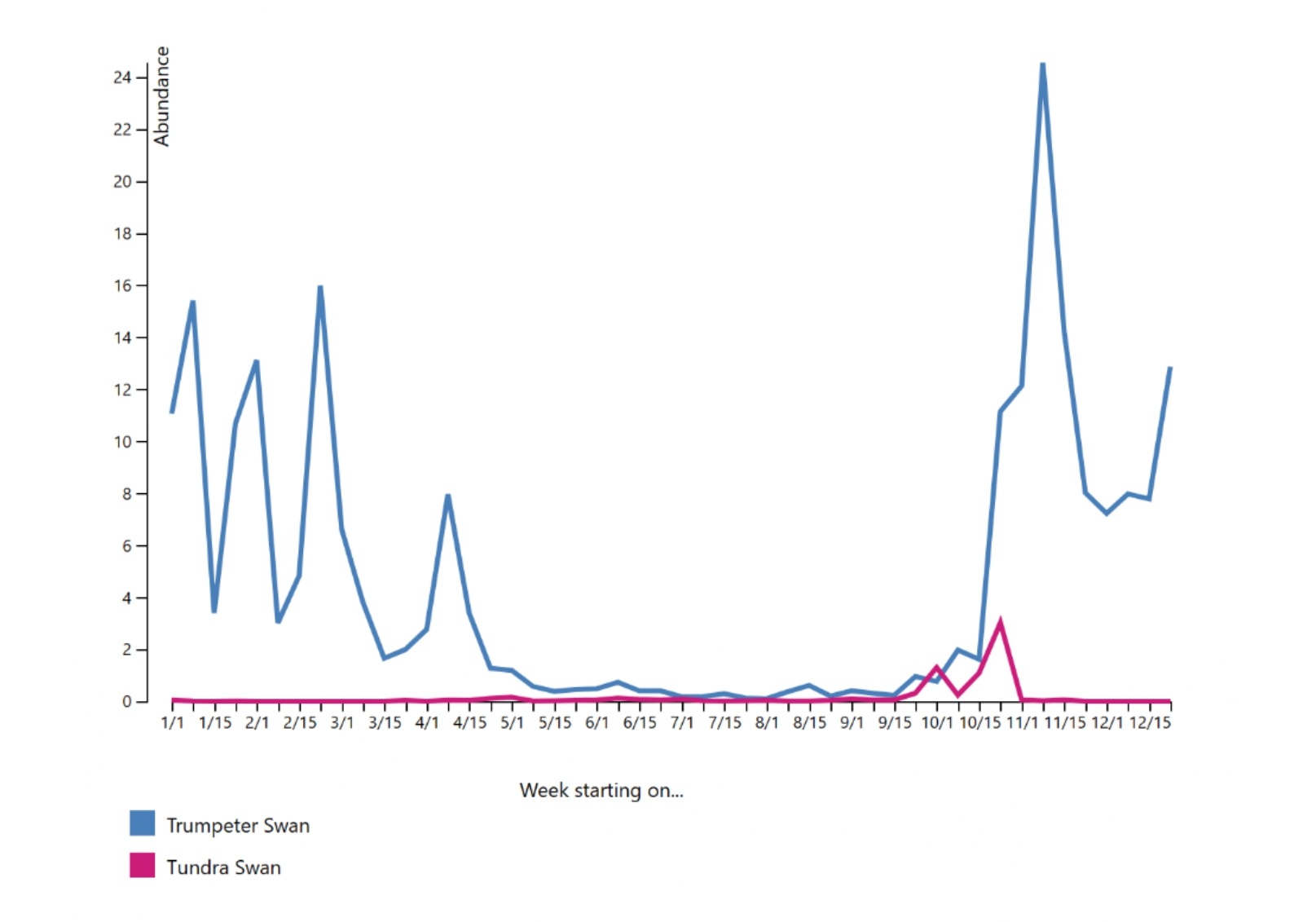

There are two species of swans that use the Chugach Region: Trumpeter and Tundra. The Trumpeter Swan nests in the region, particularly on the forested lowland lakes of the western Kenai Peninsula. This population has historically wintered in the Washington-Vancouver area, particularly in Skagit Valley, but many now winter over in the Chugach Region. In contrast, Tundra Swans nest in treeless tundra much further north in Alaska but occasionally pass through the Chugach Region during the fall migration. They are common migrants and casual summer and winter visitors to the Chugach Region.

The Trumpeter Swan is the heaviest bird native to North America, and the largest living waterfowl with a wingspan of 6–8 feet and a bill measuring around 4–5 inches. Trumpeter Swan cygnets are dusty gray with pink legs, and their plumage will become solid white with black legs as adults. Their bills are black with a pale salmon-pink color lining their mouth. Both species are frequently stained rusty orange, particularly around the head and neck, from feeding in areas with high iron concentrations in the water.

Tundra Swans (C. columbianus) are much smaller than Trumpeter Swans, but they are similarly white in plumage with a black bill. However, Tundra Swans have a yellow-colored patch atop their beak. They can also be distinguished by their call. Trumpeter Swans were named for their loud, trumpet-like call, whereas Tundra Swans have a higher-pitched call that sounds like a whistle.

Tundra Swan

or Qugyuk (LCI), qaturyuaq (PWS), GAXtl’ (Eyak)

Illustration by Kim McNett

or uquerpak (LCI), uquirpak (PWS), GAXtl’ (Eyak)

Illustration by Kim McNett

Habitat and Status

Trumpeter Swans prefer breeding areas that are quiet lakes, slow moving rivers, and wetlands in forests. They like to nest in shallow marshy water, where they have enough space to take off and easily accessible food. These swans usually mate for life and will come back each spring to use the same nesting location for the next several years. The female will lay 2–12 eggs that can be up to 5 inches long, the largest egg of any flying bird currently alive. The male spends most of his time guarding the nest while the female incubates the eggs. After 32–37 days, the young will hatch. The cygnets will be able to swim soon thereafter but will not fledge for 3–4 months. The time between when the young hatch and when they fledge is a very vulnerable time for them. After this period is over, their chance of survival is very high. In the summer, the adult swans will molt which will leave them unable to fly for the following month.

Unmated Trumpeter Swans tend to gather on lakes within their breeding area while the mated swans will be near their nesting site. In the fall, sometime between September and October, they will migrate south in small flocks or family units. When gone from Alaska for the winter they are known to land in agricultural fields to ear grains or other small plants.

Tundra Swans are a common migrant and a casual summer and winter visitor to the Chugach Region.

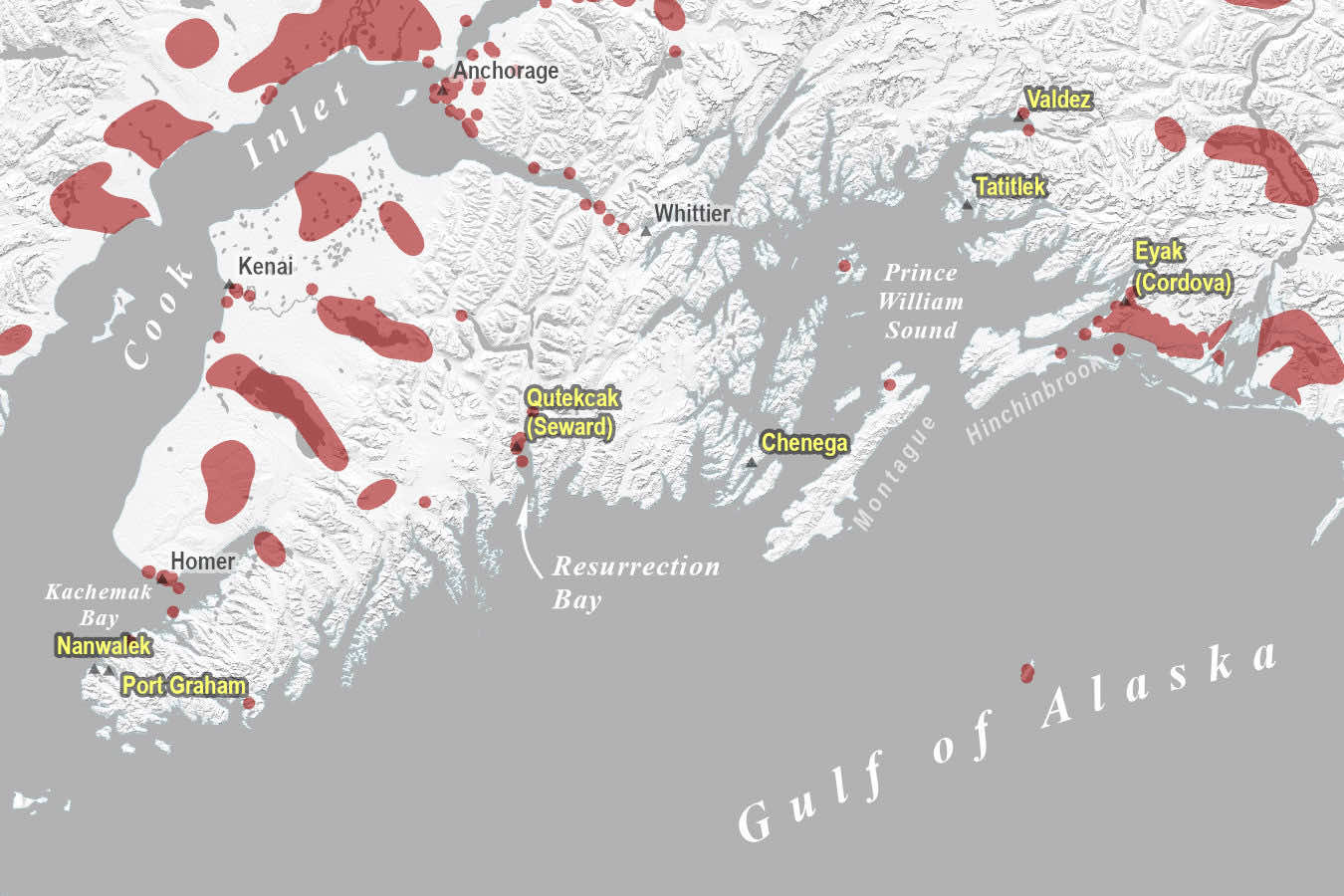

Threatened with extinction only a few decades ago, Trumpeter Swans have made a remarkable comeback, now numbering almost 6,000 pairs in Alaska. The number of nesting pairs on the Kenai Peninsula has increased from 20 to 50 in the past 6 decades (Morton 2016). Audubon’s climate model projects a 67% loss of the current winter range by 2080, with a dramatic shift northward projected, particularly in the Chugach Region. This forecast is consistent with recent observations of increasing numbers of Trumpeter Swans wintering over in Prince William Sound and on the Kenai Peninsula. In contrast, Tundra Swans’ breeding and wintering ranges are forecasted to decrease by 2080 (Audubon Society 2019).

Distribution of Tundra Swans, which occasionally migrate through the Chugach Region in the fall.

Distribution of Trumpeter Swans, which nest and increasingly winter, in the Chugach Region.

Traditional Use

Like many other birds in the Chugach region, swans were hunted for food. They are not one of the main food sources but help supplement a diet high in fish and marine mammals. Swans were among the bird species whose bones were found in substantial quantities in an archaeological investigation on Yukon Island in Kachemak Bay. The Eyak also historically hunted swans on the Copper River Delta by community members collaboratively driving flocks ashore while they were molting and unable to fly away. Akaran (1981) wrote that Lt. Abercrombie witnessed such an event in 1884, in which flightless birds were forced ashore, trapped, and killed with clubs by Eyak villagers.

Swan metacarpals were used to make awls. The swan metatarsal was used to make a fine scraper, with the distal end preserved as the handle (de Laguna 1975). The hollow wing bones of swans were also used to make drinking tubes like a straw, sometimes as part of a special practice when girls reaching puberty were secluded in a special hut for a time (Birket-Smith and de Laguna 1938). Similarly, boys had blowguns made of the wing bone of an eagle or swan, from which they shot small darts (Birket-Smith and de Laguna 1938).

Swans’ white feathers were used for decoration. The well-known feature of decorating hair with loose eagle or swan down has a typical northwestern distribution in North America and is often solemn. Potlatch dancers often carried two eagle or swan feathers in each hand or a whole eagle tail (Birket-Smith and de Laguna 1938).

Continue Your Search Below