Arctic Tern

Sterna paradisaea

Interested in reading the “Bird Ethnography of the Chugach Region” book?

Arctic Tern

Sterna paradisaea

ayusaq (Lower Cook Inlet), nerusiculiq (PWS), K’uunch’iyah (Eyak)

Description

Terns have long, gray wings and webbed feet. They are generally smaller than gulls and more trimly built with sharp-pointed bills and forked tails. Because of their tails and their agility and quickness in flight, terns have sometimes been called “sea swallows.” They are quicker than gulls and can hover. They rarely go far in the air without flapping their wings. Terns fly with their bills pointed down at right angles to the water. Because their webbed feet are small, terns don’t swim well and are seldom in the water longer than it takes to catch a mouthful of food. Most of the fish they eat are immature shore-dwelling juveniles of larger ocean species, such as capelin, cod, and herring. Krill is a diet staple, and they will also eat crab when the opportunity presents itself (ADF&G).

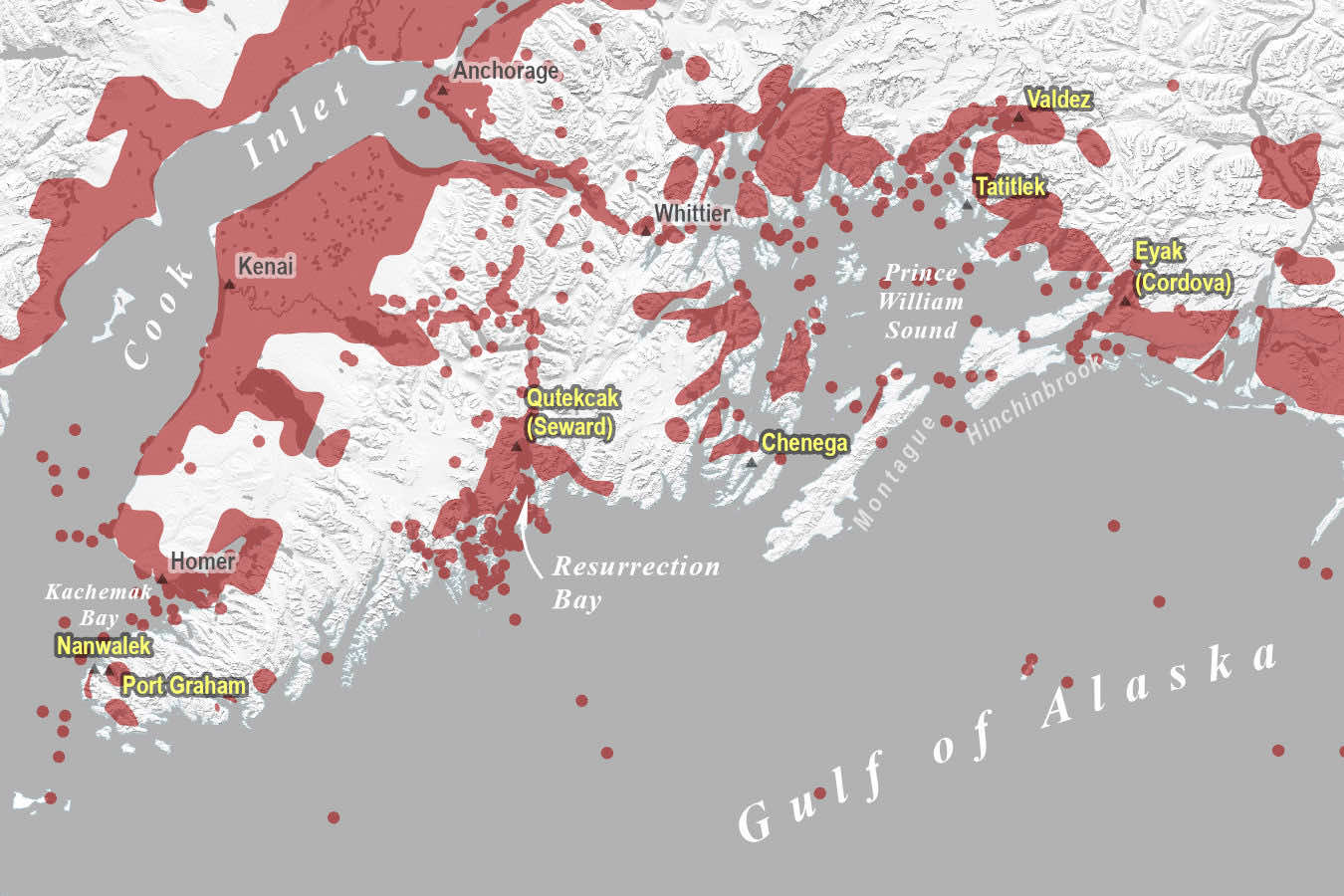

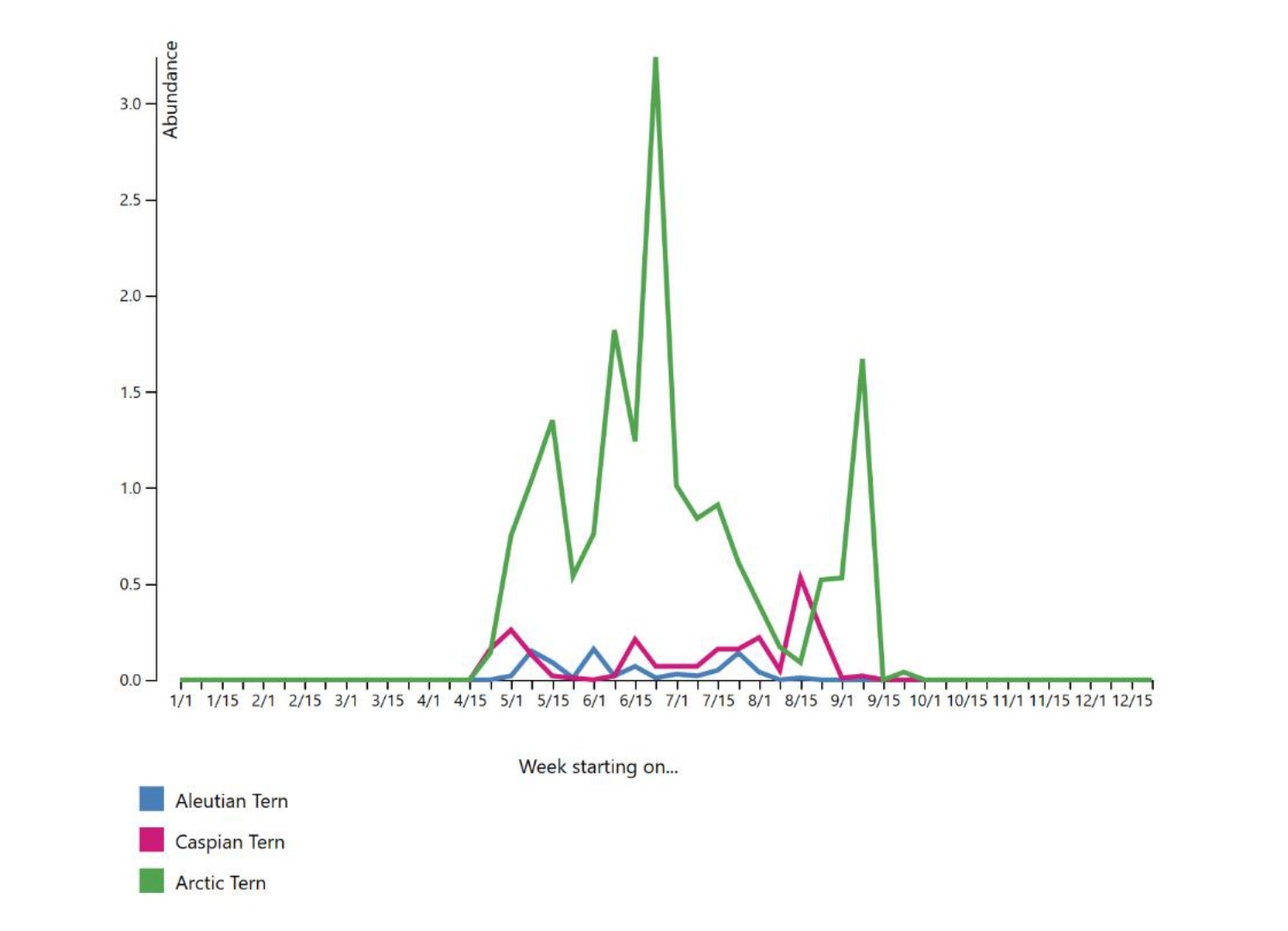

The Chugach Region is home to the Arctic, Aleutian (Onychoprion aleutica), and Caspian (S. caspia) terns. Arctic Terns are by far the most common of the three, widely distributed along coastal areas of Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound during summer. They are 11–15 inches long, with a 26–30-inch wingspan and a forked tail. They have a small white and gray angular body and bright red feet and bill. The very similar Aleutian Tern has a white forehead whereas Arctic Terns have the full black cap. Caspian Terns have black legs and a red bill and are much larger than the other two species. They are quite rare in Alaska, although sightings have increased in recent years and there is now a small breeding colony in the Copper River area.

Arctic Terns are the ultimate snowbirds, experiencing two summers each year and no winter. They migrate from their summer breeding grounds in Alaska to a second summer in Antarctica. They migrate over 44,000 miles in an average year, flying as much as 50,700 miles. Despite spending summer on both poles, the polar oceans are frigid, and much of the tern’s time is spent on the Antarctic ice shelf. Arctic Terns have relatively shorter legs than other tern species, suggesting this may be an adaptation to life associated with low temperatures.

Arctic Tern or ayusaq (Lower Cook Inlet)

or nerusiculiq (PWS) or K’uunch’iyah (Eyak)

Illustration by Kim McNett

Habitat and Status

The Arctic Tern is an abundant migrant and abundant breeder in the Chugach Region. Some Arctic Terns live 30 years. They mate for life but only nest every one to three years. Breeding doesn’t begin until the third or fourth year of life. Terns arrive at their breeding areas in early to late May. They choose mates and begin nesting very soon thereafter. Nests are commonly made near fresh or salt water on sandpits, beaches, and islands or inland on wet tundra and near ponds. Nests are little more than shallow depressions scraped in the ground with little or no lining material. A tern’s nest is almost impossible to spot unless it contains eggs. Two eggs are usually laid, lightly speckled, and brownish or greenish in color.

Both sexes incubate them, and the eggs hatch in about 23 days. The chicks will fledge 21–24 days after hatching. Juveniles learn to feed themselves after fledging, including the challenging plunge-drive. The young leave the nest quickly and hide in the neighboring vegetation. They are fed small fish which have been caught and carried to them in their parents’ bills. After about 25 days the young have fledged and are able to fly and forage, including the challenging plunge dive. Less than three months after their arrival, most terns left the breeding areas and started migrating. The young terns will migrate south with some help from their parents.

Arctic terns are abundant and widely distributed in the Chugach Region during summer months. They do not appear to be directly impacted by a warming climate, but the foods that make up their diet may be. Warming waters and ocean acidification can affect krill.

Arctic Terns are well distributed in the Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound.

Traditional Uses

Native elders tell stories of harvesting gull and tern eggs halfway between Chenega and Valdez on Fairmont Island in Prince William Sound. Most people reportedly ate the eggs fresh rather than preserve them. Pete Kompkoff, a Chenega elder, thought that tern eggs were better than “seagull” eggs (Kompkoff 1992).

Eyak villagers traditionally recognized the imminent arrival of King salmon by the arrival of terns (Birket-Smith and de Laguna 1938).

Continue Your Search Below