Barrow’s and Common Goldeneyes

Bucephala islandica, B. clangula

Interested in reading the “Bird Ethnography of the Chugach Region” book?

Barrow's and Common Goldeneyes

Bucephala islandica, B. clangula

qapugnaq (LCI), qatert’snat (PWS)

Description

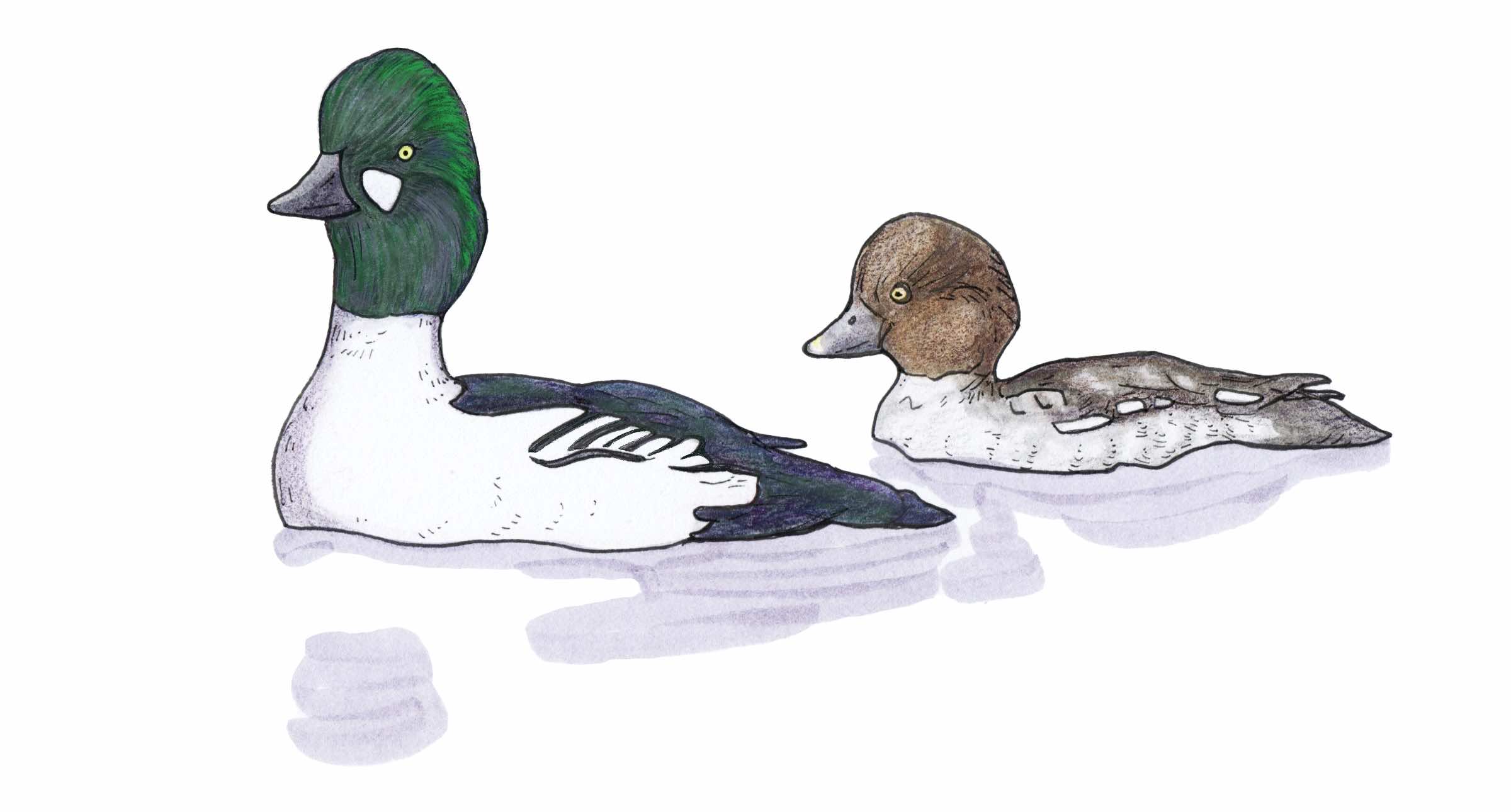

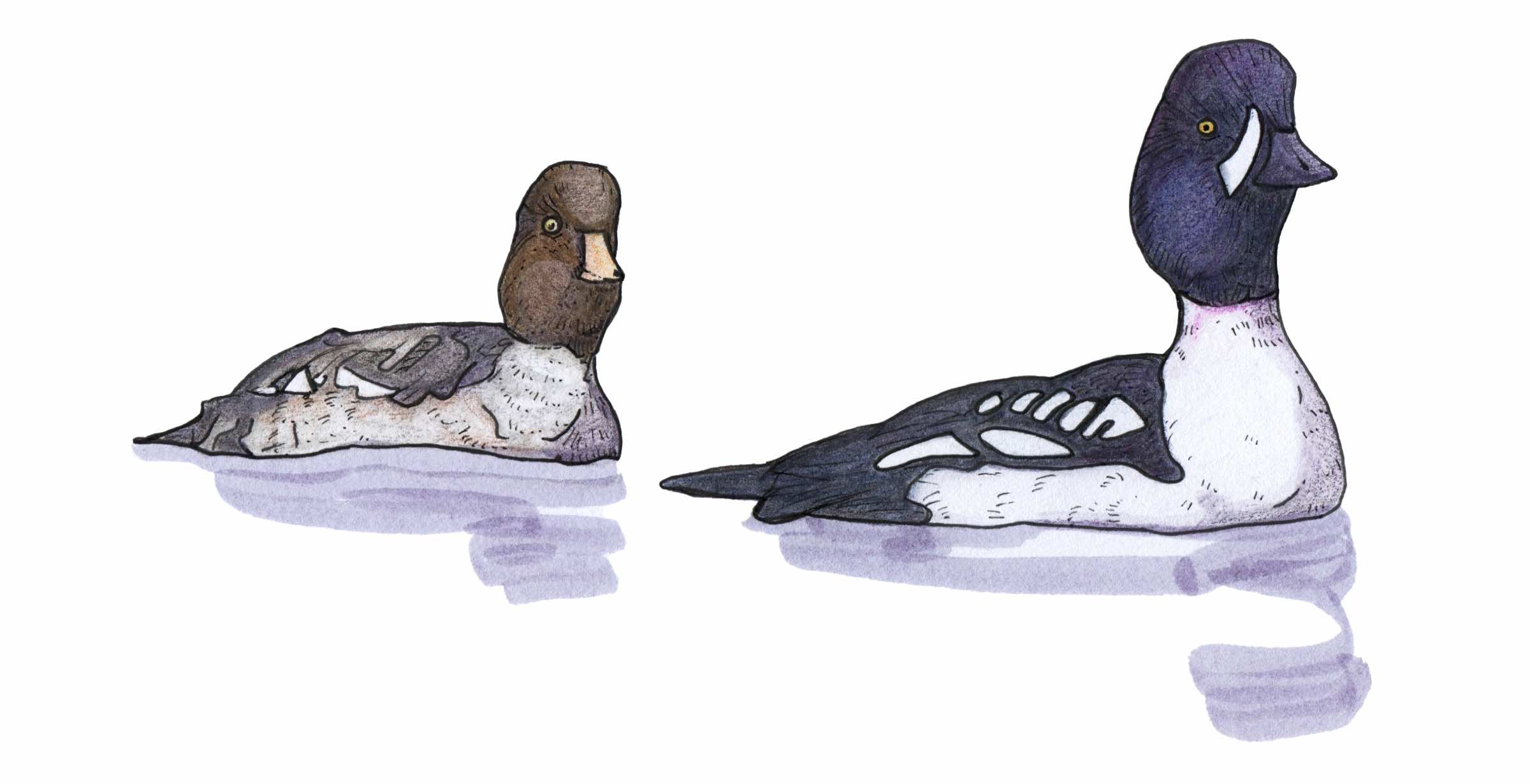

As the name suggests, goldeneyes have bright yellow-gold eyes that stand out against their dark head feathers. There are two species that use the Chugach Region: Barrow’s and Common Goldeneye. Barrow’s Goldeneye can often be seen in the same flock as Common Goldeneyes. A key difference is the steep forehead on Barrow’s Goldeneyes, rather than the sloped forehead on Common Goldeneyes. Male Barrows have a dark blue-purple sheen to their head rather than green, and a crescent-shaped white patch behind the eye. Their heads are also slightly rounder than the angular triangle shape on the Common. Barrow’s Goldeneyes have a bright white chest and belly with black wings and back. Barrows have white patches along their wings, with small white spots in a row. Female Barrow’s Goldeneyes have the same chocolate brown head as Commons, but it matches their brown and white body more than the contrasting cold gray of Common Goldeneyes.

The male Common Goldeneye appears mostly black and white, but in the right light the head shines a deep green. Behind the eye is a small white dot, and on the black wings are strips of white. The female Common Goldeneye have a warm chocolate brown head that contrasts their grayish body, as well as a dark bill with a yellow tip.

Illustration by Kim McNett

Illustration by Kim McNett

Habitat and Status

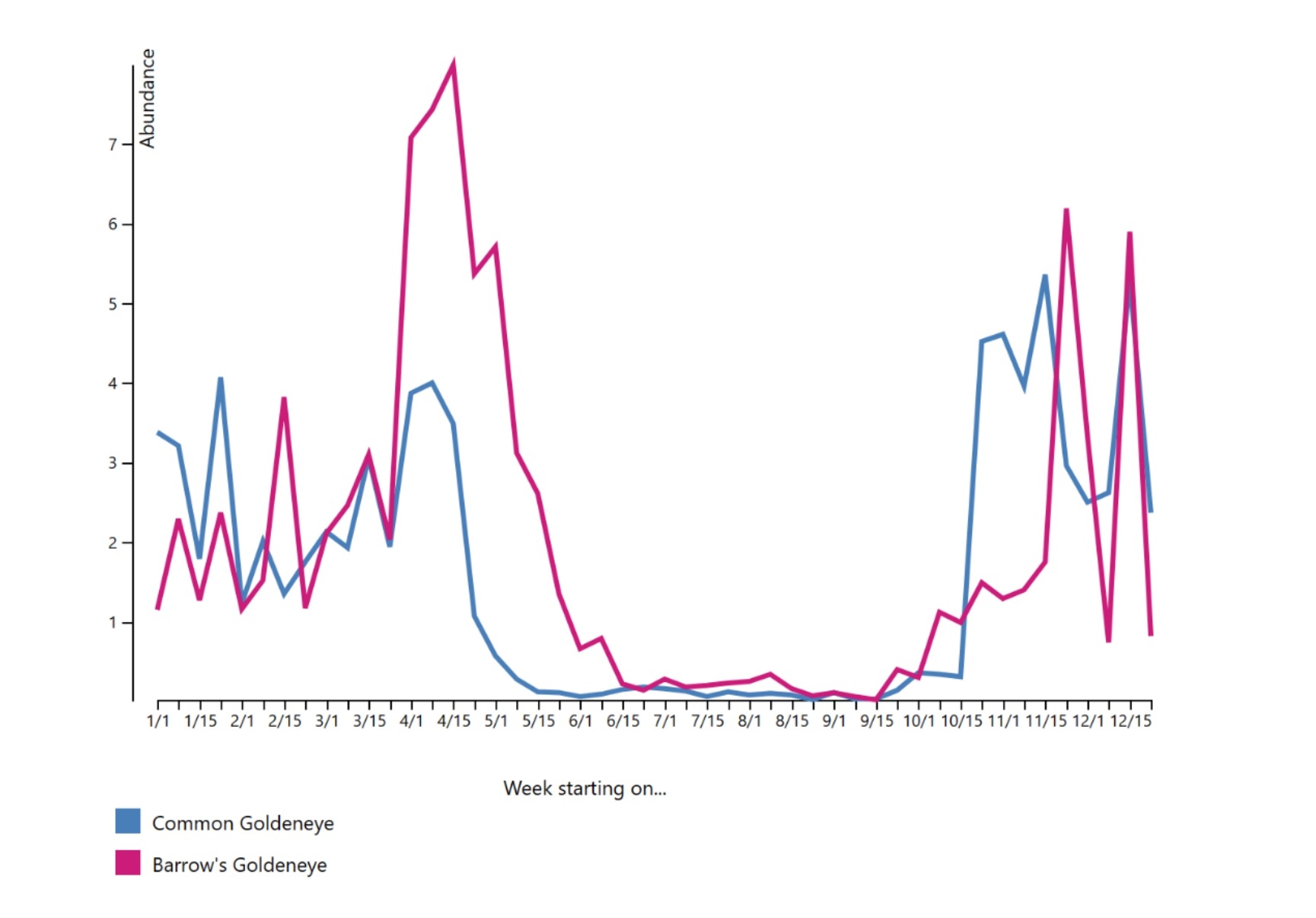

The Barrow’s Goldeneye is a resident of the Chugach Region, occurring seasonally as a common migrant, a common breeder, and an abundant winter resident. The Barrow’s Goldeneye outnumbers the Common Goldeneye, except locally along the coast during migration and in some of the fjords in winter. Spring migrants are common along the outer coasts. During the spring breeding season, goldeneyes can be found in quiet wooded ponds and lakes. They often return to the same site every year with their mate until the molting season. During the molting season, they will travel to specific remote wetlands or marshy sites where they will be flightless for 20‒40 days. Barrow’s Goldeneyes have been known to stay as mating pairs even though they may be separated for an extended period each summer during molt.

In the aftermath of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, goldeneye’s wintering habitat was impacted, exposing the birds to oil in the shallow water along the coast where they feed. The oil spill decreased the population of goldeneyes along the coast, and hydrocarbons persisted in their tissues for two decades. In more recent years, surveys indicate that populations have recovered. Prince William Sound now supports 20,000‒50,000 Barrow’s Goldeneyes during the winter.

Audubon’s climate models suggest that the summer range of Barrow’s Goldeneyes is likely to decrease by 86% and its winter habitat by 59%. In contrast, the summer and winter ranges of Common Goldeneyes are likely to increase by 29% and 36%, respectively, by 2080.

Barrow’s Goldeneyes are widely distributed year–round throughout the Chugach Region, particularly during winter.

Traditional Use

One Elder from Cordova appreciated that goldeneyes winter over, particularly in Prince William Sound. “I love goldeneyes…we hunt those in the wintertime because I do a lot of winter king fishing out here, and if you get bored or something and you got your shotgun onboard, you can run up into a bight and shoot a couple golden eyes. Boy, they’re fat and real pretty birds. So, you get a couple, not that many a month, but a couple and you roast them up” (Jansen 2001).

Continue Your Search Below