Canada and Dusky Canada Geese

Branta canadensis and B. canadensis occidentalis

Interested in reading the “Bird Ethnography of the Chugach Region” book?

Canada and Dusky Canada Geese

Branta canadensis and B. canadensis occidentalis

temeggiaq (LCI), temngiaq (PWS), naaXAg (Eyak)

Description

The Canada Goose is one of the more well-known goose species. Both sexes have a black head and neck with bright white cheeks and a band across the chin. The rest of its body is various shades of brown, besides its pale chest and belly. Because there are so many Canada Goose subspecies in the Pacific Flyway, they can vary 25–45 inches in length, wingspans can reach 75 inches, and weights can be up to 12 pounds.

Dusky Canada Geese are the darkest and one of the smaller subspecies of Canada Goose. They have a warm brown breast and body, hence the name “dusky,” which contrasts with the buff breast and mottled gray body of other subspecies. Duskies are often more wary than some of the other subspecies, flying low and inspecting a potential area to land before descending.

or temeggiaq (LCI), or temngiaq (PWS), or naaXAg (Eyak)

Illustration by Kim McNett

Habitat and Status

The Canada Goose is a resident of the Chugach Region, occurring seasonally as an abundant migrant, locally abundant breeder, and locally uncommon winter resident. Canada Geese nest from the Bering River area and the Copper River Delta, and their drainages westward through Prince William Sound to the adjacent upper Cook Inlet region. They appear to be largely absent from the western North Gulf Coast. A few to several hundred Canada Geese winter on the tidal flats of several of the bays, inlets, and fjords of Prince William Sound – apparently the northernmost wintering geese in North America (Isleib and Kessel 1973).

Dusky Canada Geese, which only breed in the Chugach Region, require wetlands for nesting and foraging and so are found near rivers, lakes, and marshes. Duskies pair for life and begin producing eggs at 2–3 years of age, generally laying 4–5 eggs. During the mating season, the goose (male) may become highly territorial and aggressive, even toward other Duskies. The rest of the year, Duskies are social animals and will fly, rest and feed in large groups. They molt their wings during early July to early August. Often, molting individuals will wait in subalpine lakes for their feathers to grow back.

Breeding populations occur on the Copper River Delta and, more recently, Middleton Island, exceeding 100 nests per square mile in some areas. Prior to 1964, the low elevation of the delta and periodic flooding during high tides maintained broad expanses of sedge meadow dissected by a reticulated pattern of drainage channels and sloughs. Early surveys showed that Duskies

selected mixed forb/low shrub nest sites along slightly elevated slough banks, and that flooding was the major cause of nest losses. The 1964 Alaska Earthquake lifted the delta by 2–6 feet, damaging usable breeding grounds. Rapidly expanding shrubs and trees were favorable to brown bears, coyotes, foxes, and bald eagles, significantly increasing predation on nests and adult geese. Duskies started colonizing Middleton Island in the early 1980s.

Historically, midwinter population indices for Dusky Canada Geese were much higher than they are today, exceeding 26,000 birds in 1975. The population declined steeply in the early 1980s, falling below 10,000 birds as effects of the 1964 Alaska earthquake accelerated changes to breeding ground habitat on the Copper River Delta. Starting in 1983, more than 860 artificial nest islands of different designs were installed on the Copper River Delta to deter nest predation. Almost four decades later, Duskies numbered almost 18,000 (circa 2019). However, with ongoing forest succession on the delta and associated predation, impaired production will likely limit the population of dusky geese for the long term.

Cordova Elder Bud Jansen offered nuanced observations that mostly support Western science. “Well, with the change, the raising of the land, I shouldn’t say the drying up of the delta, but thechanging in the nesting patterns, mother nature is going to take care of itself, and these geese are going to move off. Now we got coyote problems…and the influx of eagles, you know, it’s just phenomenal with eagles, so you have two major preys on the geese and goslings.”

Audubon’s climate modeling suggests little change for Canada Geese in the Chugach Region (Audubon Society 2019). However, high predation pressure by bears, coyotes, foxes, and bald eagles may continue to depress populations on the Copper River Delta. In addition, changes in food abundance and availability on wintering grounds such as agricultural croplands could affect mortality and survival rates, although the impacts of climate change on these habitats are unclear.

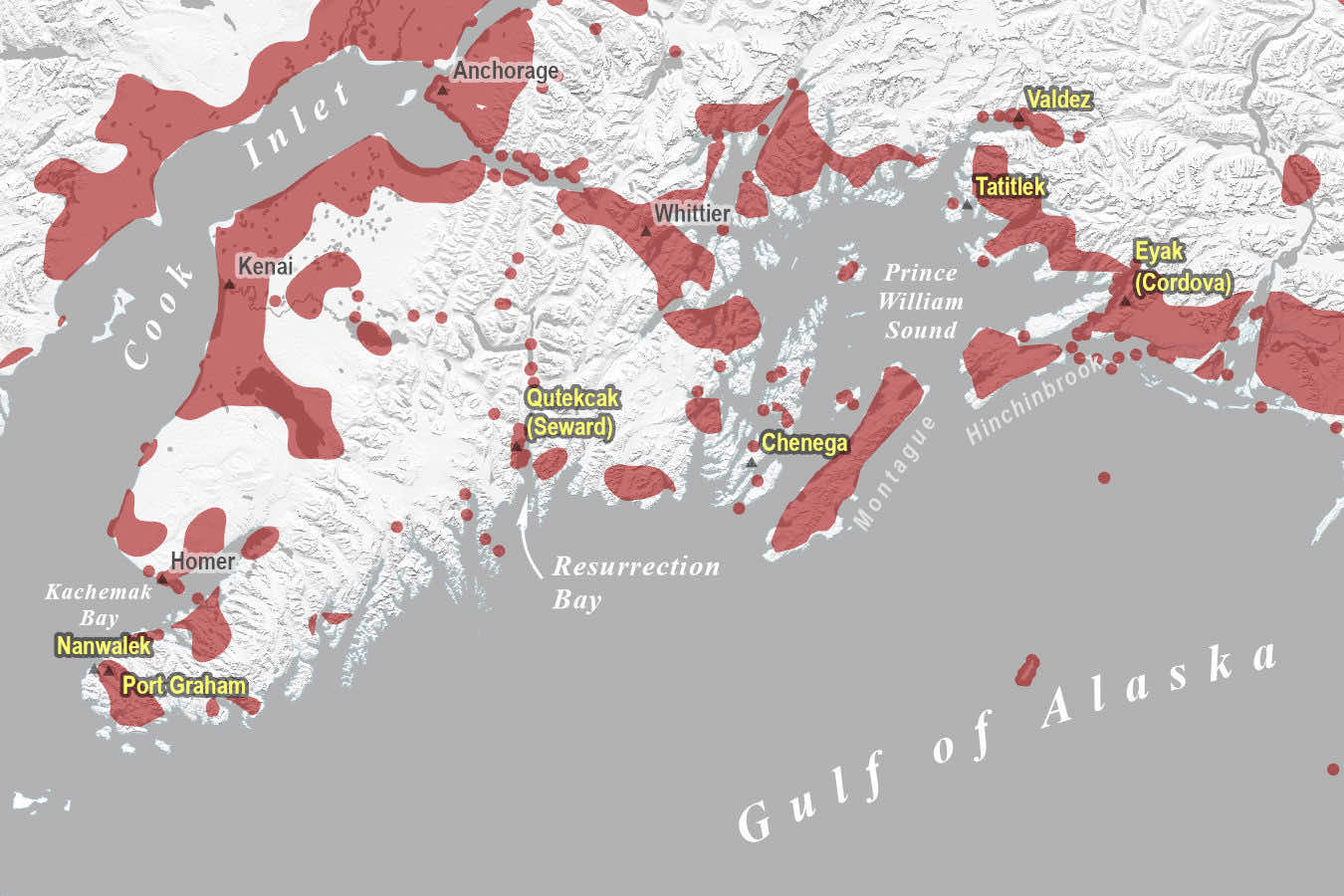

Distribution of Canada Geese and Dusky Canada Geese in the Chugach Region. The breeding population of Duskies is almost exclusively on the Copper River Delta and Middleton Island. The Anchorage area supports several thousand nesting resident Canada Geese.

Traditional Use

Geese are, and have been, an accessible food for Chugach people, particularly on the Copper River Delta. But they serve many other needs as well. Their large hollow bone tubes were decorated and used as awls, needle cases, drinking tubes, and perhaps for storing beads (de Laguna 1956, 1975). Contemporary Elders recall that families used soft, warm goose down to stuff pillows and mattresses. Bird down is also an excellent fire starter. Despite the variety in species, Elders report that all geese “taste the same!” (Alutiiq Museum).

Geese have been hunted by the Chugach people from prehistory through the present (Akaran 1981). A 1932 archeological excavation on Yukon Island in Kachemak Bay revealed many geese that had been taken by snares, slingshots, and bows and arrows. An ingenious Alutiiq goose snare in the Smithsonian Museum’s collection is fashioned from wood, baleen, and leather. It features a slippery loop of baleen tied to a set of wooden stakes. The stakes were set in the ground, and the loop was left to catch a bird’s head, foot, or wing. Alutiiq people set these snares along the shores of ponds and marshy areas where geese fed (Alutiiq Museum).

The Eyak people historically used sharp-pointed arrows and clubs to harvest molting geese in August, when geese were incapable of flight. All the inhabitants of the village would join in driving geese along the sloughs to a narrow place where they could be forced ashore and killed by simply wringing their necks. The best time for these drives was in the early morning or evening. Lieutenant Abercrombie witnessed one harvest in which villagers encircled flightless geese on the mud flats near Alaganik, killing them with 2-foot-long clubs, round in section but narrowed for a grip with a knob at the end of the handle, like a baseball bat (Birket-Smith and de Laguna 1938).

Although geese are much more plentiful in the Chugach Region during the fall migration, hunting for them during that season may be a legacy of modern waterfowl harvest regulations that, until very recently, prohibited spring take under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Anthropologist Kaj Birket-Smith (1953) was told that “Men and boys played with bows and arrows after the wild geese had returned [to Prince William Sound] but stopped in the autumn”.

In reminiscing about harvesting in more modern times, one Elder from Cordova said, “We never really shot any bird in the spring; it was always in the fall because that was the hunting season. I always wanted to hunt in the spring because there are a lot of birds like…Speckle Bellies [Greater White-fronted Geese] or Yellow Legs that come in the spring are really hard to get in the fall. Snow Geese come through; they are harder to get in the fall. But we never did do it; we hunted birds in the fall.”

On the other hand, it makes good sense to collect eggs and hunt in the spring. “Say, we’ll have a two-week season, the last week in April, the first week in May, and go from there…And that way if you just have a short season in the spring, you are not going to target that many Duskies. I know local people who don’t have access to Egg Island or anywhere else where your Speckle B Bellies and everything else are flying, though they will probably drive out the road and end up taking a couple of Duskies. People will do it, but that way, you’re working in good faith, showing that you’re not trying to wipe out the Dusky population. Set it up, so you must take them both if you see a pair. Just like you’re only allowed so many fish if you subsistence fish. But it allows people to do it.” And as one Elder offered about harvesting both geese and their eggs: “Geese, yeah. Lotsa geese before, too. Those got big eggs ‒ just like Ostrich eggs!” (Borodkin 1981).

In the past, people ate eggs fresh or stored them in pits for future use. Elders remember cooking eggs and other fresh foods in hollowed-out cottonwood logs on the beach. They dropped hot rocks from a campfire into the log to heat water for cooking. Before refrigeration, people stored eggs in grass-lined pits to keep them cool but unfrozen throughout the winter. Upright sticks marked these pits so they could be easily located (Alutiiq Museum). John Klashnikoff once stated that at Nuchek and Makarka Point, bird eggs were stored in a barrel of seal oil to preserve them for the winter.

Continue Your Search Below