Common Loon

Gavia immer

Interested in reading the “Bird Ethnography of the Chugach Region” book?

Common Loon

Gavia immer

tuullek (LCI), tuullek (PWS), yehs (Eyak)

Description

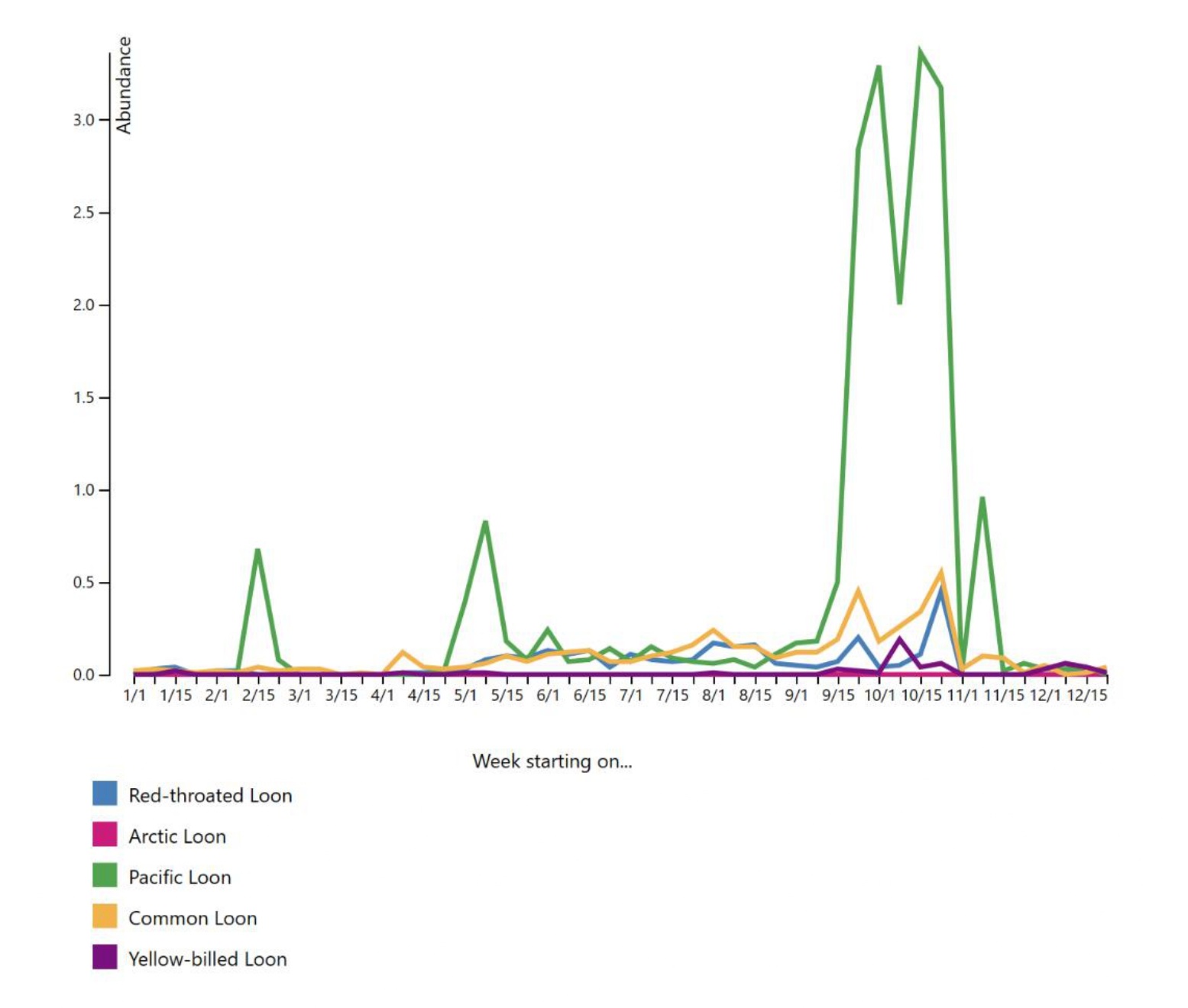

Loons are excellent swimmers and divers, using their webbed feet that are set far back on their bodies to propel themselves above and below water. However, loons have difficulty walking and avoid being on land except to mate and nest. Loons tend to point their heads slightly upwards while swimming but droop them more than similar aquatic birds in flight. In addition to the Common Loon, four other loon species use the Chugach Region: Pacific (G. pacifica), Red throated (G. stellata), Yellow-billed (G. adamsii), and Arctic (G. arctica). All five species are uniquely different in both the way they sound and look.

Common Loons have a black head and bill with deep red eyes. Around their necks are rings of black and white stripes that lead to a white chest and spotted black and white body. A Common Loon’s song is quite eerie, a long wailing cry that echoes across lakes. Loons also have shorter calls that are softer, used often by parents to keep in contact with their young.

Adult and immature Common Loons

or tuullek (LCI) or tuullek (PWS) or yehs (Eyak)

Illustration by Kim McNett

Habitat

The Common Loon is a common resident of the Chugach Region. Spring migrants are common throughout inshore waters and on larger lakes. Breeders occur on most of the larger, upland lakes within the forests and woodlands of the region. Common Loons are fairly common on saltwater adjacent to their coastal breeding lakes, visiting the coast to feed on small fish. Common Loons are abundant during winter in the more sheltered bays and inlets.

Common Loons arrive at their breeding grounds at the end of May. Their nests made from vegetation and lake debris can be found along shorelines of lakes and similar bodies of waters. The female will lay two eggs that both parents will take turns incubating. Loons are excellent divers and will typically choose to dive rather than fly if they feel threatened.

Status

Audubon models suggest that both summer and winter ranges of the Common Loon are expected to shift northwards in a warming climate. In the Chugach Region, wintering populations may fare better than breeding populations of Common Loon (Audubon Society 2019).

Common Loons are widely distributed year-round in the Chugach Region.

Traditional Use

A loon skin (or a raven’s foot) was thought to possess magical power and might be worn as amulets to bring good luck for hunting sea otters. A loon’s breast was sometimes used to make unsewn caps (Birket-Smith 1953).

Loons are considered lucky in the Arctic, where they are admired for their speed and sharp vision. To foster these qualities in their children, Alaska Natives often placed newborn babies on loon skins. A Chugach legend illustrates this tie to keen vision and explains how the loon got its white breast (Alutiiq Museum).

A blind boy went to a lake where he heard a Loon calling. He asked the Loon to cure his eyes, the Loon called a second time but much closer to the boy. “Crawl on my back, hold me tight and don’t let go. I am going to dive with you.” The Loon dove into the water with the boy and swam around the lake five times. When the boy and the Loon came up, the boy could see. The boy told the Loon to wait for him to return so he could give him a gift. The boy returned with an apron made from Dentalium shells, and this is the reason Loons have white breasts.

The Blind Boy and the Loon – by Makari Chimovitsky

Another possible interpretation of this story is that Dentalium shells were given high value if they were placed on par with something so precious as one’s sight. Dentalium shells are the curved, white, tusk-shaped shells of scaphopods; they are hollow and open at both ends and so can be strung together. These shells were sewn into hats and used in beaded earrings, bracelets, necklaces, headdresses, and nose pins. They were so valuable that a pair of delicate Dentalium shells could be traded for an entire squirrel skin parka (Alutiiq Museum).

Trade in Dentalium shells is also well-documented, with shells traveling great distances from the Northwest Coast to places like interior Alaska, Kodiak, and the Aleutian Islands. Chugach people fished for Dentalium in the Copper River area. One gruesome account is that Tlingit near the Charlotte Islands, as observed by a Russian Naval Officer, harvested Dentalium by immersing a human corpse in the water for several days; when they retrieved the body, Dentalium would be clinging to it! Pebbles incised with drawings of people more than 500 years ago seem to show Dentalium shell necklaces (Alutiiq Museum).

Another story told of a boy who transformed into a loon. This boy told the Chugach people living in Sheep Bay that a nearby lake with no obvious outlet was actually connected to the ocean by an underground channel, which explained why their speared fish sometimes disappeared (Birket-Smith and de Laguna 1938).

Continue Your Search Below