Common Murre

Uria aalage

Interested in reading the “Bird Ethnography of the Chugach Region” book?

Common Murre

Uria aalage

(no Alutiiq/Sugpiaq/Eyak translation)

Description

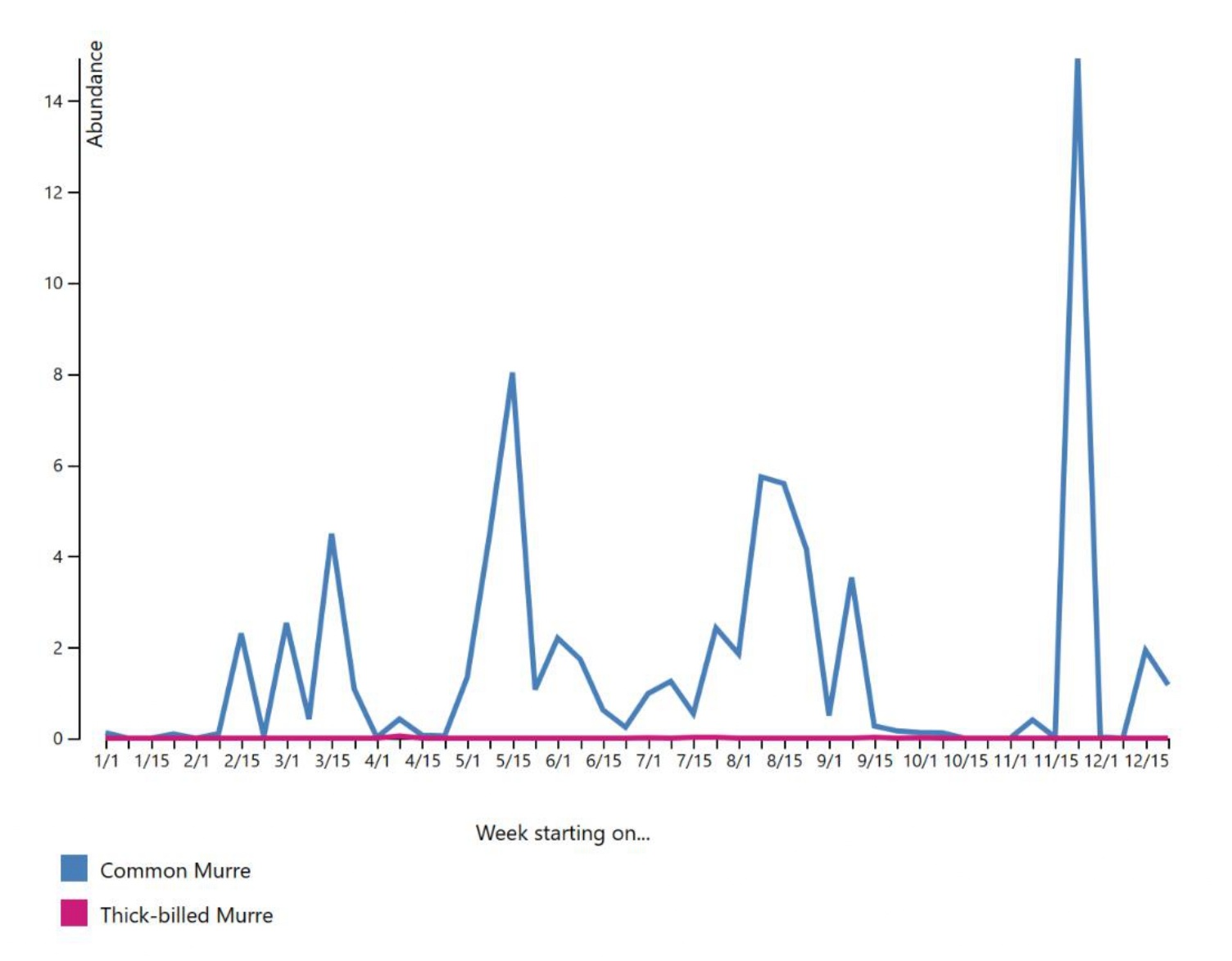

The Chugach Region is home to two murre species, Common Murres and Thick-billed Murres (U. lomvia). Murres are pursuit divers, which means they forage for food, primarily fish, by “flying” underwater with very short wings relative to their body size. This body configuration also means they work hard to fly, with rapid wing beats that sound like a helicopter rotor lifting through the air. They are more graceful underwater and typically dive to depths of 100–195 feet, though dives of up to 600 feet have been recorded. Common Murres are indeed common and widely distributed throughout the Chugach Region, whereas Thick-billed Murres are relatively rare.

Common Murres are 15–18 inches in length, with a 24–29-inch wingspan. They are black on the head, back, wings, and tail and white on the remaining underparts. Their bill is thin and similarly colored to its head. In contrast, Thick-billed Murres are slightly larger than Common Murres, measuring 16–19 inches in length, with a wingspan of 25–32 inches. In Europe, they are called Brünnich’s Guillemot. Otherwise, they are very similar to Common Murres, but they have a thin white stripe by their bill and, as the name suggests, a thicker bill. Males and females of both murre species are nearly impossible to distinguish in the field.

Illustration by Kim McNett

Habitat and Status

The Common Murre is a common resident in the Chugach Region. They are locally abundant at sites along the outer coast. Like other auks, Common Murres spend their time out at sea unless it’s breeding season. During summer, they come to shore and nest along rocky cliffs in dense colonies, except they don’t build nests. The Common Murre lays a single egg directly onto the rock ledge, its somewhat triangular shape encouraging it to roll in a circle instead of rolling off the cliff. Eggs range from white or brown in color to various shades of blue and green, some with speckling or lines or no markings at all. Why the eggs come in such a variety is still unknown, but one theory is that it allows parent murres to recognize their own egg amongst other eggs sharing a ledge. The egg hatches after 30 days, and after just 10 more days, the chick can regulate its own body temperature. The chick will follow its male parent to sea after only 20 days, while the female stays at the nesting site for another 14 days. The fledged chick cannot fully fly yet but will glide through the air and into the water. Though they cannot fly, as soon as the chicks are in the water, they’re able to dive for food.

Worldwide, murres have been dying off in large numbers. Dead murres showed signs of starvation, but why murres cannot find food is still undetermined. About 4 million common murres died in response to the 2014‒16 marine heat wave that occurred in the northeast Pacific including the Gulf of Alaska, representing half of Alaska’s common murre population (Renner et al. 2024). The 2020 Gulf of Alaska Ecosystem Status Report, produced by NOAA Fisheries, describes the ecological effects of two recent extended marine heatwaves that are still evident in the Gulf of Alaska and are thought to have contributed to decreasing Common Murre population counts in Cook Inlet and abandoned nesting colonies of black-legged kittiwakes around Kodiak (Ferris and Zador 2020).

Distribution of Common Murre in the Chugach Region.

Traditional Use

There is not much known about the traditional uses of murres, but they have been found at historic sites in Kachemak Bay with signs of being hunted by snares, slingshots, and bow and arrow (Akaran 1981).

Continue Your Search Below