Glaucous-winged Gull

Larus glaucescens

Interested in reading the “Bird Ethnography of the Chugach Region” book?

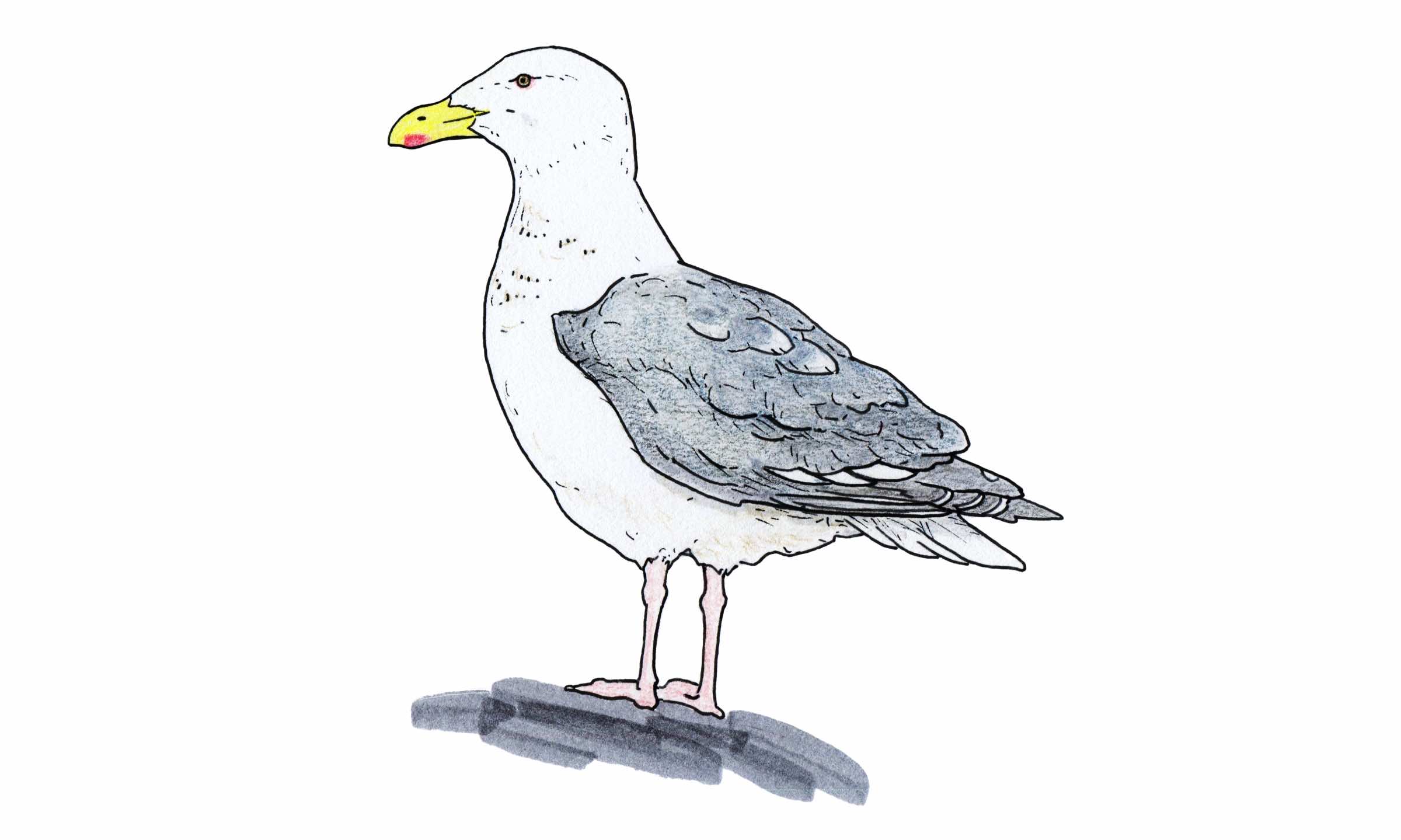

Glaucous-winged Gull

Larus glaucescens

Naruyaq (Alutiiq), k’uLdiyaann (Eyak)

Description

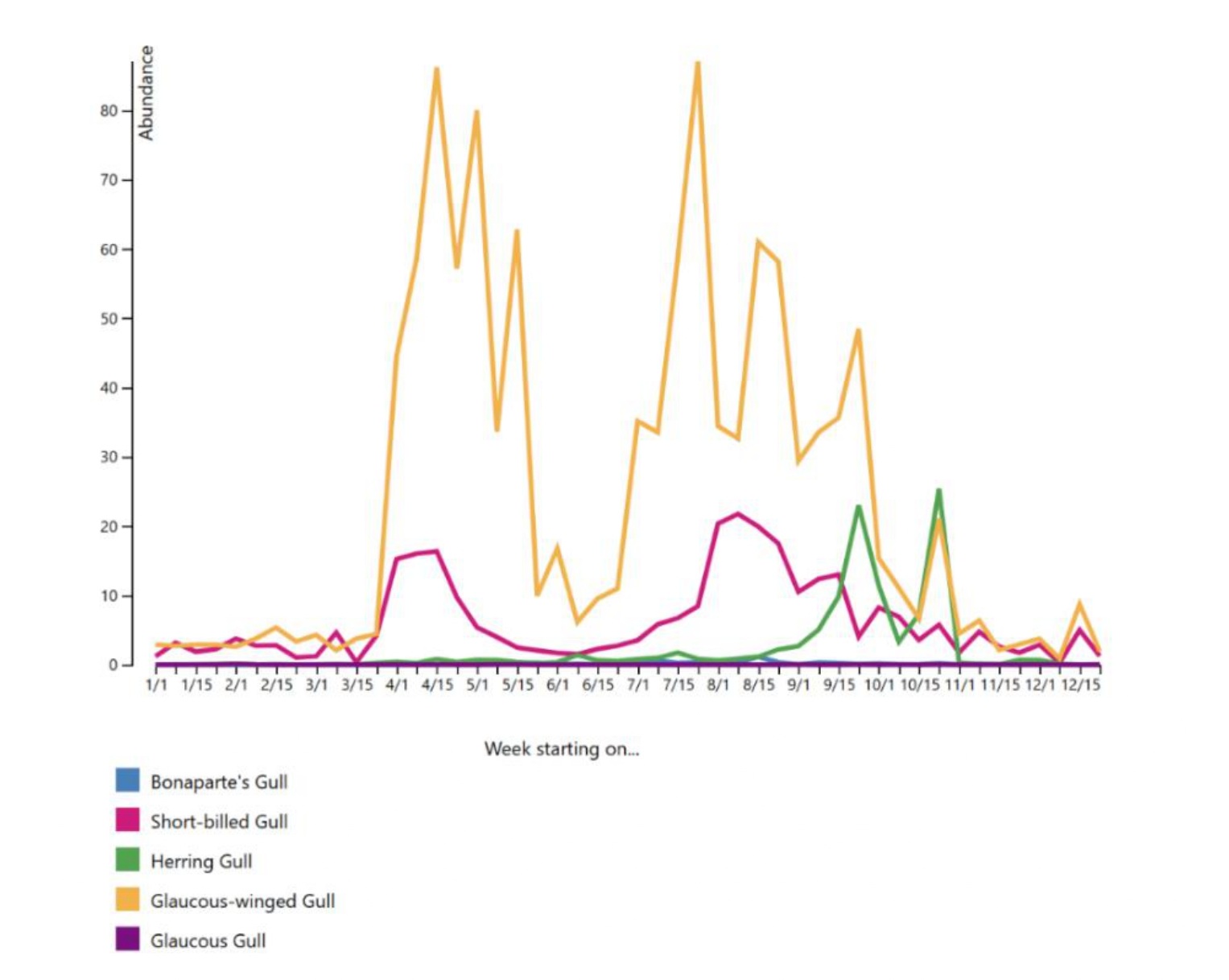

There are three species of large Gulls in the Chugach Region: Glaucous-winged, Glaucous (L.hyperboreus), and Herring (L. argentatus). These gulls are so closely related that hybrids are known to occur, and Alutiiq and Eyak people do not appear to distinguish them, calling all of them naruyaq or k’uLdiyaann, respectively. Short-billed Gull (L. canus [formerly Mew Gull]) and Bonaparte’s Gull (Chroicocephalus philadelphia) are two other common, but smaller, gulls. Only the Short-billed Gull was given the unique Eyak name of uch’Axtsin’da’dAt’uuch.

Glaucous-winged Gulls are known as the common “seagulls” along the southern coast of Alaska, certainly in Prince William Sound where they are present year-round, in large numbers, and well distributed. This appears to have been historically true, too. In the early 1930s, “sea gulls, in particular the Glaucous-winged Gull, [were] seen daily” in Prince William Sound. This gull is 23–26 inches in length and usually lives about 10 years. They have white heads and bodies, with gray backs and wing tips, pink legs, brown eyes, and a red spot on the bottom on their yellow beak. The juveniles are a dark brown-gray and, over their first four years, the color will lighten until they gain their adult plumage (Birket-Smith 1953).

Glaucous-winged Gull or k’uLdiyaann (Eyak)

Glaucous-winged Gulls are scavengers but are also known to eat live fish, and eggs or chicks of other bird species. They are semi-migratory birds, usually present in Alaska year around but may disperse south or spend more time at sea during the winter. Towards the end of winter and into early spring they will return to their colony site.

Illustration by Kim McNett

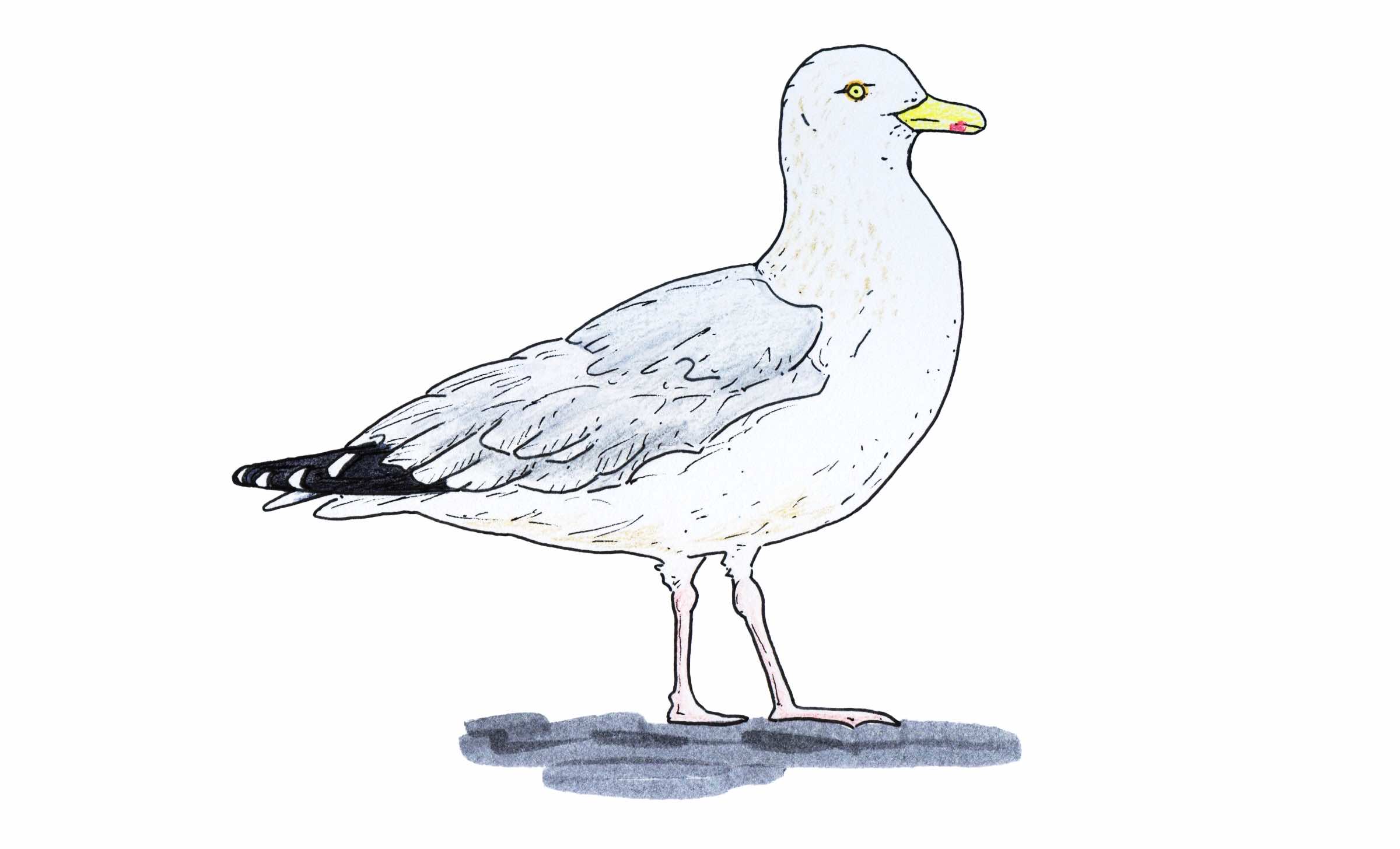

Herring Gull

They have a red dot on the lower bill like Glaucous and Glaucous-winged Gulls, yellow eyes like the former and gray back like the latter, but they also have black wing tips with small white spots.

Illustration by Kim McNett

Short-billed Gull

They look like a smaller version of Herring Gulls, but with dark eyes and yellow legs.

Illustration by Kim McNett

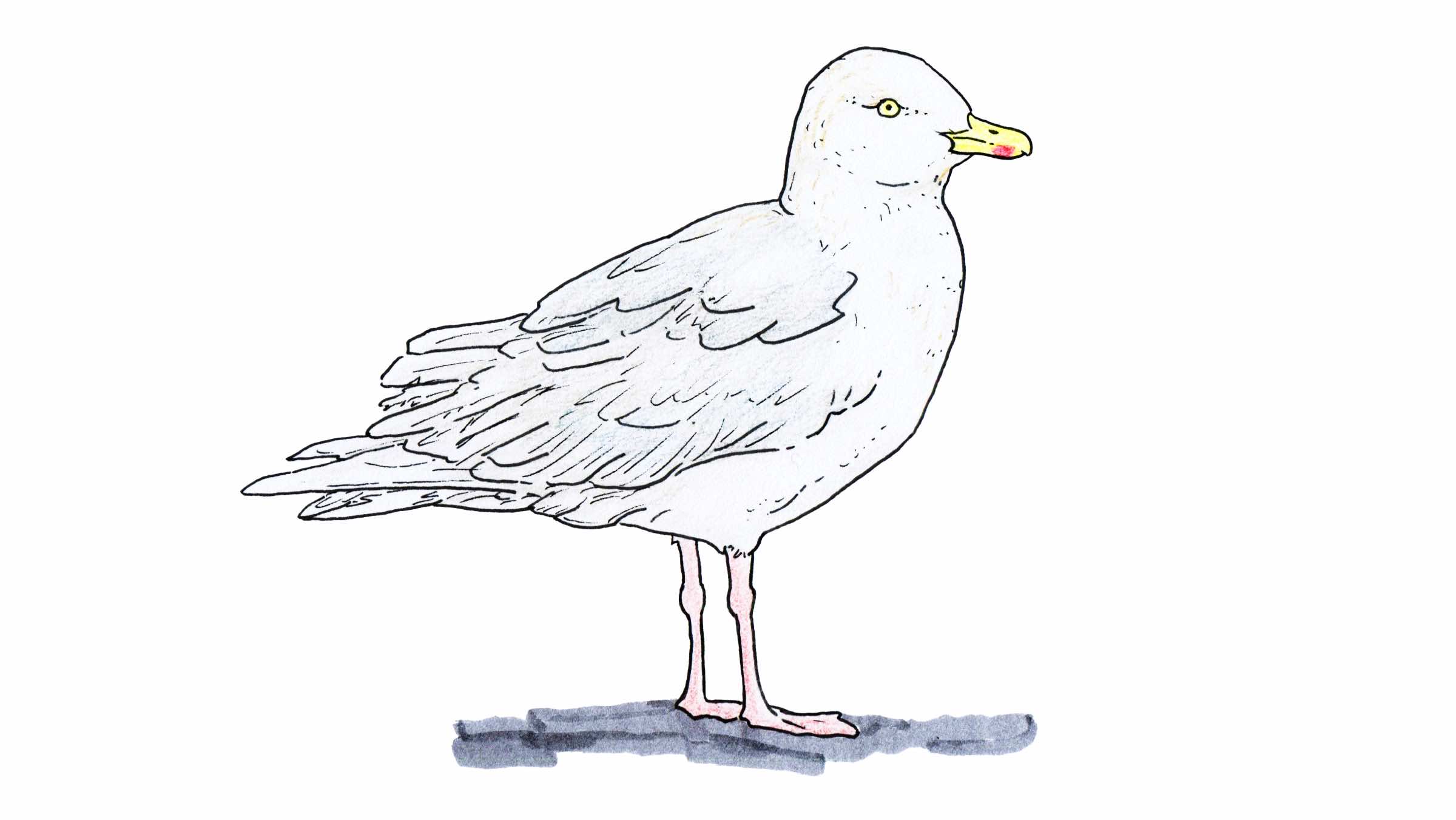

Glaucous Gull

They are larger than Glaucous-winged Gulls and have yellow eyes but no dark wing tips. They are relatively uncommon in the Chugach Region, mostly visiting in spring and fall.

Illustration by Kim McNett

Bonapart’s Gull

Bonaparte’s Gulls are easy to recognize from the others with their black head, black tipped tail, and red legs. They are the only gull that commonly nests in trees, particularly Black Spruce.

Illustration by Kim McNett

Habitat and Status

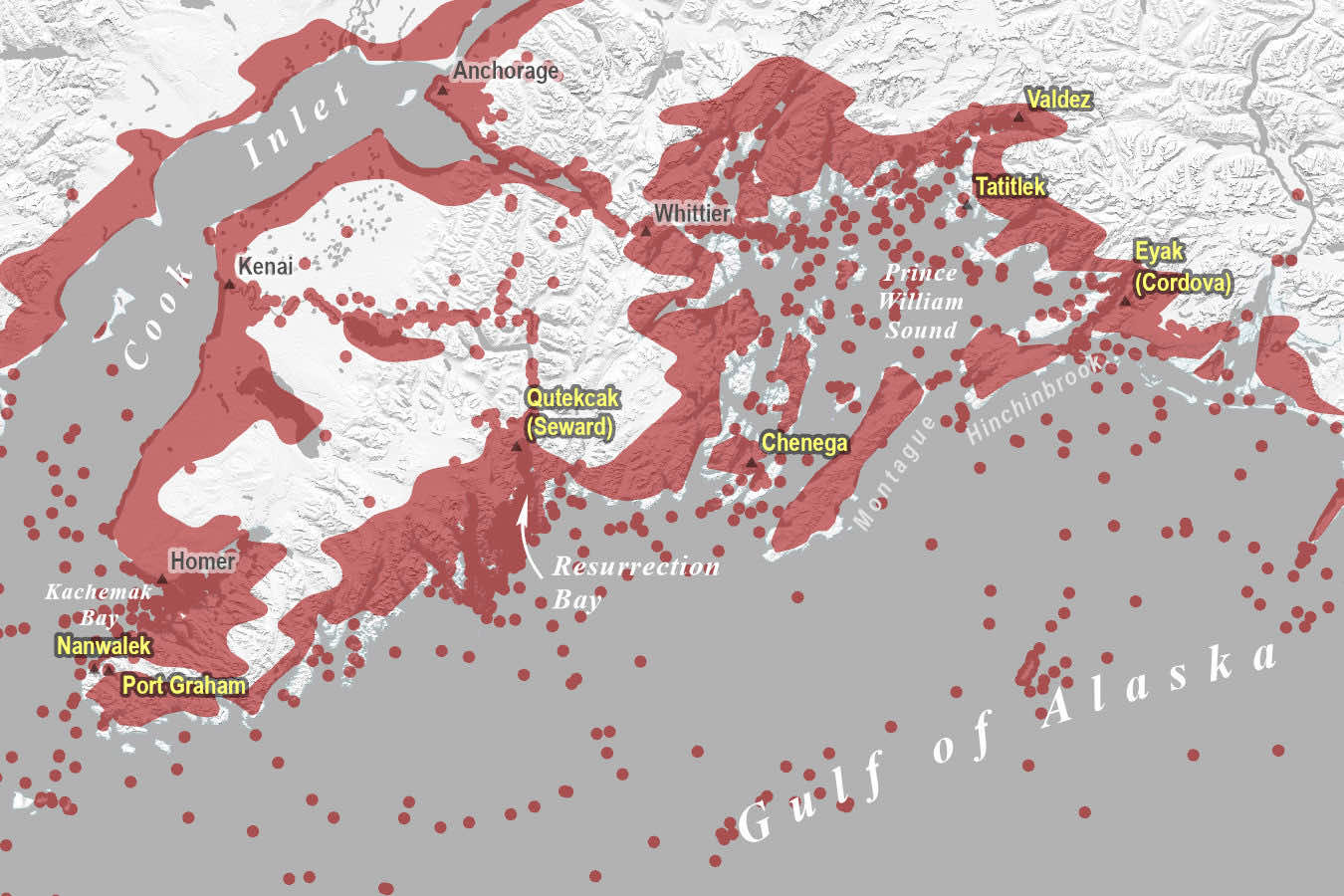

Glaucous-winged Gulls are widely distributed through the Chugach Region. They live mainly in intertidal coastal areas but will sometimes follow rivers or salmon streams inland. They also go out to sea, especially during the winter months. Because they scavenge, they will congregate at natural food sources and man-made sites. For example, a large colony nests and roosts at the mouth of the Kenai River but makes daily flights to forage in the Soldotna landfill. Colony sites are typically grassy hillsides, but they will nest in other places as well. Colony sizes can range from less than a dozen pairs to 10,000 pairs. They lay a clutch of 1-3 eggs in mid to late May and, by late June, the chicks will have hatched (ADF&G).

Glaucous-winged gulls currently breed along the coast from the Bering Sea south to Puget Sound. The world’s largest Glaucous-winged Gull colony is on Egg Island in Prince William Sound. Climate modeling by Audubon suggests little change in the Chugach Region. However,climates over coastal areas of the Arctic Ocean across North America are forecasted to become more favorable for breeding Glaucous-winged Gulls by 2080.

Distribution of Glaucous-winged Gulls in the Chugach Region

Traditional Use

Gulls in general, and certainly the ubiquitous Glaucous-winged Gull, were snared and hunted in the Chugach Region. A 1932 archeological excavation on Yukon Island in Kachemak Bay revealed that various bird species, including gulls, were hunted with snares, slingshots, and bow and arrow. Gulls (and ducks) were sometimes taken on a gorge (ADN 2017), a single 3-pronged piece of wood or pointed stick to which a cross-stick was tied. A gorge from Chenega was pierced for the attachment of a string at the point where the three slightly curving prongs met. Gulls could also be harvested with a gull hook, essentially a large fishhook with a straight shank and a barbed or unbarbed point attached at an acute angle (Birket-Smith 1953). The Chugach also used baited traps to catch gulls and other sea birds on the water. In places where gulls and other sea birds dove for locally abundant clams, they would place a circular thong with several nooses on the surface of the water. The middle of the circle was baited with crushed clams to attract gulls (Birket-Smith 1953).

In addition to hunting and trapping gulls, the Chugach harvested sea gull eggs in large quantities, preserving them for the winter. Each spring, gulls lay many thousands of eggs on inaccessible cliffs and rocky ledges. This protects the eggs from foxes, but not from Alutiiq people on Kodiak, who have long gathered gull eggs from boats and by rappelling down cliff faces (Alutiiq Museum). Sophie Borodkin, an elder from Cordova, was quite enthusiastic about sea gull eggs, saying “Sea gull eggs. Boy! You can’t beat them for chickens [laughs]).”

The Egg Islands in eastern Prince William Sound have the largest colony of seagulls in the gulf. Yakutat and Chugach people would have competitions, wrestling, or foot races at Boswell Bay. The losers would have to go to the Egg Islands and gather eggs for the winners.

Uncooked gull eggs were traditionally stored in seal oil. According to one Chugach Elder, “They used to get sea gull eggs…Clean ’em up good, if they’re not bad, then put ’em in seal oil, and by God, December month you take a sea gull egg and crack it, it’s as fresh as the day you picked it. As long as you don’t get any air in it. Keep ’em under that oil….Wash ‘em out, and why, they could be fresh. Fresh sea gull eggs all winter long” (Klashnikoff 1979).

Gull guano was also used as fertilizer. “We would go and get the dirt under the bushes there where the seagulls would be sitting and messing and stuff and it was real good dirt so we would pack that off…for the garden, ‘cause it was real rich and had all the clamshells and you know, anything in there.” Ironically, gull eggs (and grease and blueberries) were thought to make menstruation last longer (Jansen 2001).

Gulls also provided mariners with important environmental information. Travelers know that gulls can help them predict bad weather, find schools of fish, mark currents, avoid rocks, and lead boaters to land in the fog. Flocking gulls were used to detect schooling herring in Prince William Sound and returning hooligan (Qusuuk or Thaleichthys pacificus) to streams. Gulls could also portend weather. “If the kittiwakes settle on the sea, of if the sea gulls circle clockwise, it is…a sign of bad weather; in this case the gulls are said to ‘wrap up their bedding’. If, on the other hand, they circle in the direction against the sun they are ‘getting their bedding out again’, and then the weather will be fine”. There was also a belief that it brings rain to pick seagull eggs, because that is when the gulls are laying more eggs (Birket-Smith 1953).

Continue Your Search Below