Horned and Tufted Puffins

Fratercula corniculata, F. cirrhata

Interested in reading the “Bird Ethnography of the Chugach Region” book?

Horned and Tufted Puffins

Fratercula corniculata, F. cirrhata

Ngaqngaq (Lower Cook Inlet), qilangaak/ngaqngaaq (PWS), diitinh (Eyak)

Description

Puffins are small alcids (auks) that breed in large colonies on coastal cliffs or offshore islands, nesting in crevices among rocks or in burrows in the soil. They are stocky, short-winged, and short-tailed birds with black upper parts and white or brownish-gray underparts. Their heads have a black cap and a mostly white face, and their feet are orange-red. Their bills appear large and colorful during the breeding season, which is why they are sometimes called “clowns of the sea” and “sea parrots”. They shed the colorful outer parts of their bills after the breeding season, leaving a smaller and duller beak. Their short wings are adapted for “flying” underwater; their wings are oars and their webbed feet are rudders. In the air, they beat their wings rapidly (up to 400 times per minute!), often flying low over the ocean’s surface. There are two species in Alaska: Horned Puffin (Fratercula corniculata) and Tufted Puffin (F. cirrhata).

Both species are abundant and well distributed in the Chugach Region during summer, but the Tufted Puffin is more common. The Horned Puffin is named from a small fleshy point (i.e., “horn”) above their eye that develops when they mature. A dark stripe extends back from their eye as well, which creates a contrast against their white cheeks. Horned Puffins have a black back and hood on their head, and a white breast. In contrast, Tufted Puffins have a completely black body with bright yellow “tufts” or eyebrows on top of their head.

or ngaqngaq (LCI) or qilangaak (PWS) or diitinh (Eyak)

Illustration by Kim McNett

Tufted Puffin

or ngaqngaq (LCI) or ngaqngaaq (PWS) or diitinh (Eyak)

Illustration by Kim McNett

Habitat and Status

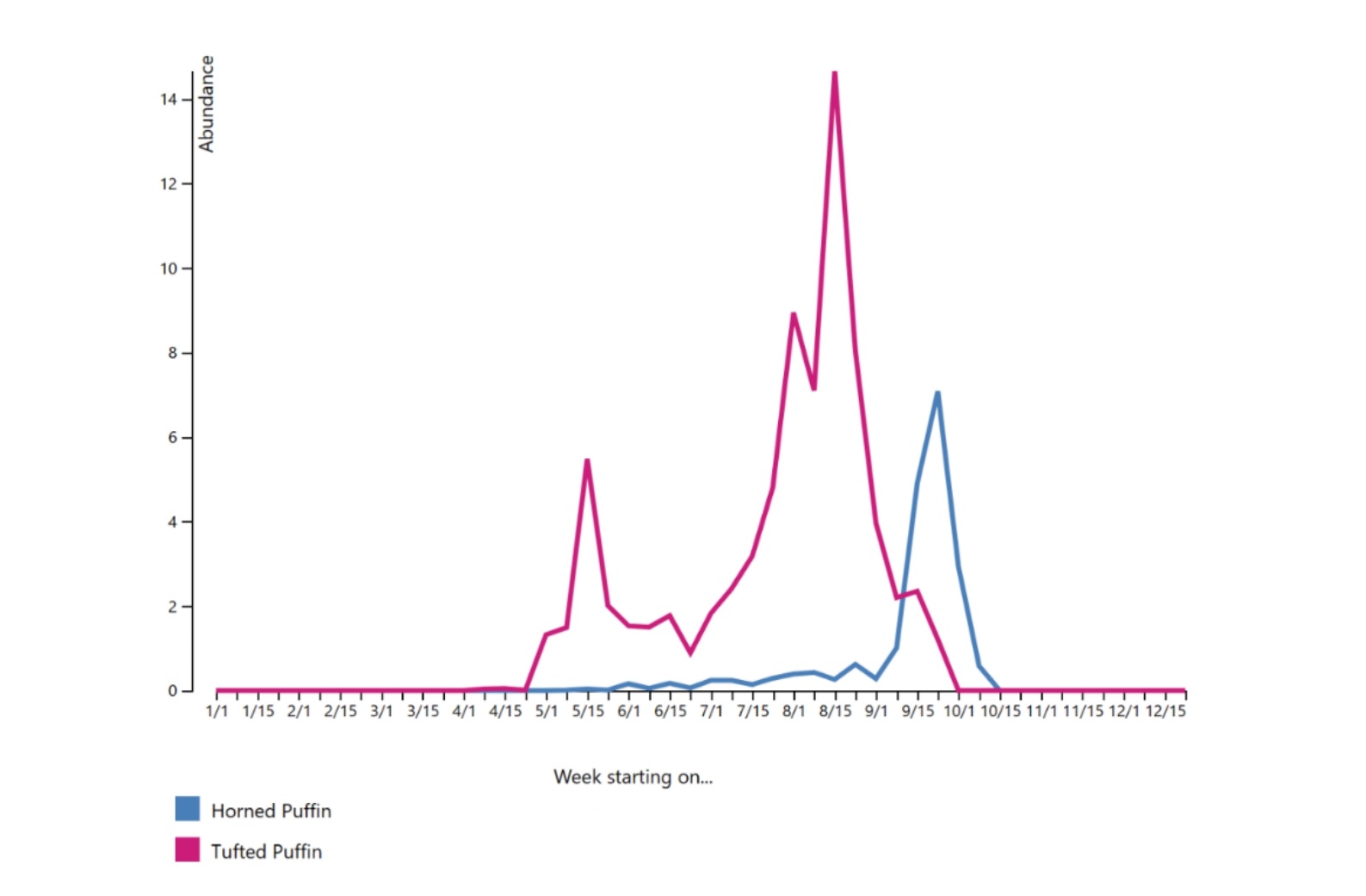

Both puffins are resident species in the Chugach Region. They nest in mixed colonies with similar birds. Tufted Puffins return to their rookeries in Prince William Sound about mid-May; Horned puffins typically follow one week later. Both begin their breeding season by gathering in large groups on the water. Puffins mate for life, and it is thought that these gatherings may reunite mated pairs. Tufted Puffins dig burrows 3–6 feet deep in the tops of islands and headlands, whereas Horned Puffins use rock crevices for nesting. A pair of Puffins will build a nest of grass and feathers where they will take turns incubating their single egg. The egg hatches after 41 days, and both parents will tend the “puffling” for another 40 days before it fledges and is ready to fend for itself.

During the breeding season, puffins are much noisier than when they’re out at sea, typically making low, guttural calls that sound like growling, purring, and wailing. People have described the Horned Puffins’ call as a “distant sound of a chainsaw.” After breeding, puffins spend most of the year out at sea. Their waterproof feathers make it extremely easy for them to live at sea, where they dive for fish, small invertebrates, crustaceans, worms, and squid or small algae on occasion. Both species of puffins are likely to be impacted by the changing ocean currents and the vulnerability to changes in prey availability near breeding sites.

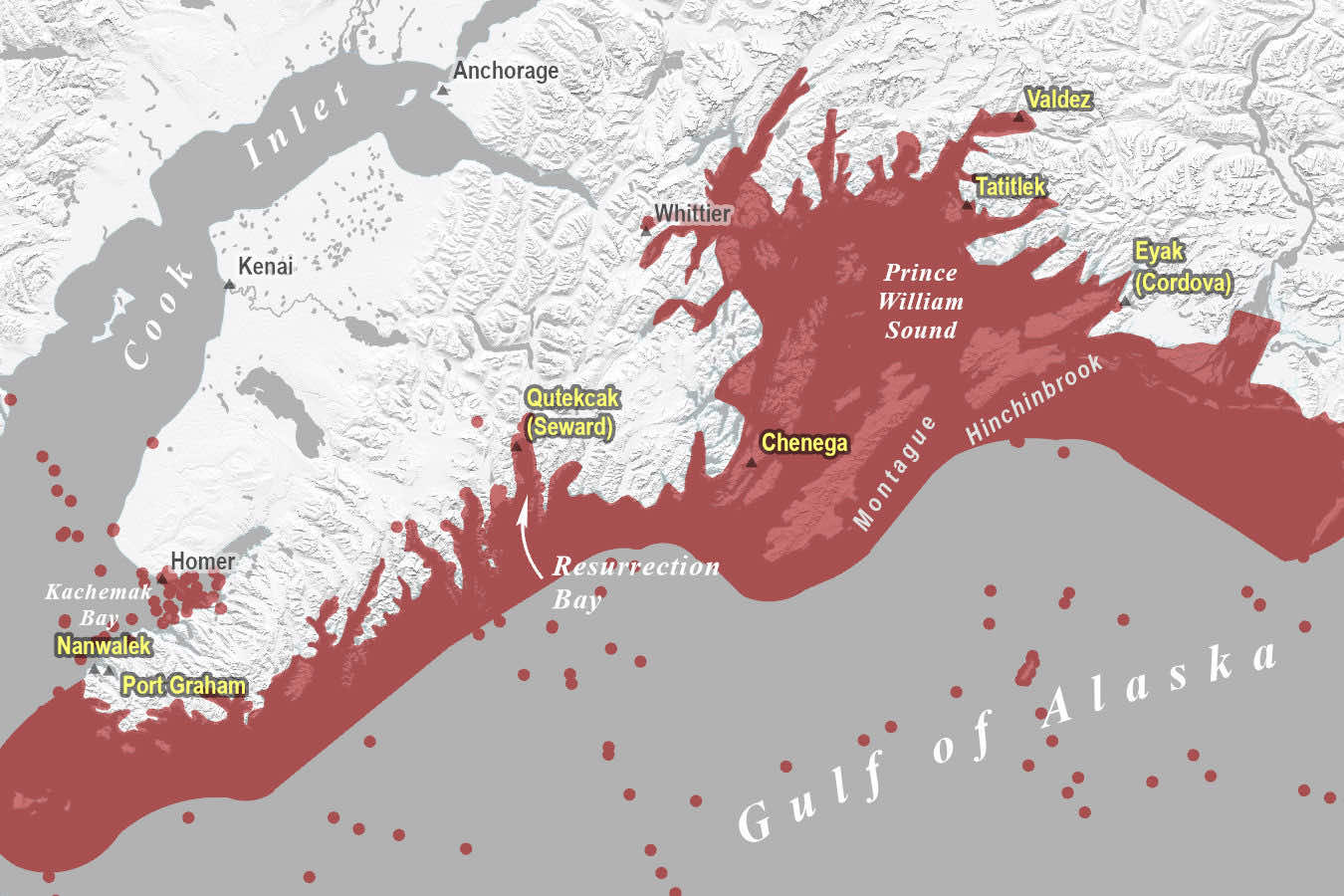

Horned Puffins are well distributed in marine waters of the Chugach Region.

Tufted Puffins are well distributed in Prince William Sound, but only sparsely in the Cook Inlet.

Puffin beak rattle on display at the Ethnological Museum Berlin. Photo collected by the Ilanka Cultural Center / Native Village of Eyak in October 2023.

Traditional Use

Horned and Tufted Puffins, or “Sea Parrots,” were one of many birds taken for food in the Chugach Region, although it’s not clear if their eggs were commonly harvested. Although puffins are small, weighing just 1‒2 pounds, the Alutiiq people captured them for both food and raw material. The meat of the puffin is said to taste like tuna fish. Puffin skins were also one of the most common materials used for parkas that were typically worn by the poor. It took up to 60 puffin skins, complete with their white breast feathers, to make such a garment (Alutiiq Museum).

Puffin beaks were also used to make ceremonial rattles for use in ritual dances. These rattles were about 12 inches wide with up to five concentric wooden rings to which puffin beaks or barnacle shells were attached, fastened to a cross grip of thin sticks (Birket-Smith 1953). Puffin beaks were also used as ornamentation on Chugach ceremonial clothing, for example, a shaman’s apron worn during performances. It is not known whether the puffin beaks were purely ornamental or if they were believed to have some kind of power. They made a rattling noise when the shaman moved, likely part of the desired effect.

It appears that the Chugach tradition of only indulging in activities when a certain kind of bird appeared continued well into the American period. According to Nanwalek elder Irene Tanape, during her childhood, boys were only allowed to play with toy boats after the puffins arrived (Tanape 1996:Part 1). Similarly, elders also described that boys and men enjoyed swinging from ropes along bluffs in Prince William Sound, a favorite location being near the Kittiwake rocks in Boswell Bay, but the swinging only started after the puffins had returned to their colonies in the spring (Birket-Smith 1953).

In Iceland and the Faroe Islands, the Atlantic Puffin (F. arctica or Lundi) forms part of the national diet. The fresh heart of a puffin is eaten raw as a traditional Icelandic delicacy. Puffins are hunted by a technique called “sky fishing”, which involves catching the puffins in a large net as they dive into the sea.

Continue Your Search Below